An Obituary of Joan Baker 14.06.17

Peter Wakelin remembers the 'fresh, beautiful' work of a very private artist.

Joan Baker

If an artist can be both public and private, both influential and unknown, Joan Baker, who has died aged 94, is the proof. She was a formative influence on generations of students at Cardiff School of Art but during most of her seventy years of continuous painting she kept her output largely private. She had only two solo exhibitions.

Joan Elizabeth Baker was born in 1922, at home in Victoria Park in Cardiff. She was the only daughter of a ships’ engineer in Cardiff docks, Joseph Baker, and his wife Mary Harrison. After Howell’s School she won a scholarship at the age of 16 to Cardiff’s art school, arriving in the same month that war was declared. Contrary to what one might expect of wartime conditions, it was a lively period. An intimate group of students that included talents such as Glenys Cour, Bert Isaac, Glyn Morgan and John Roberts was taught by outstanding tutors: the wise and skilful Evan Charlton and Ceri Richards, already recognised as a brilliant Modernist with international connections.

Spring Evening, 1950, oil on canvas, 50x88cm, Aberystwyth University School of Art

In 1944, Joan took a post at Bath School of Art for a year then returned to Cardiff as a tutor. During nearly 40 years of teaching, some 3,000 students would pass through her hands on the introductory courses: the ‘Preliminary’ and later the ‘Foundation’. Many artists who went on to significant careers were grateful to her for helping them to be themselves, among them Ivor Davies, Ken Elias, Glyn Jones, Mary Lloyd Jones, Islwyn Watkin and Ernest Zobole. The example of Peter Prendergast stands for many. The strength of Peter’s personal vision was immediately apparent to Joan though he was clearly unsuited to some parts of the course. She fought a battle to give him a separate studio and let him choose his studies. Later, when he prepared work to submit to the Slade but realised that he couldn’t afford to send the crate to London, Joan gave him the £5 he needed – about a third of his father’s weekly wage as a miner.

Her attitude to shaping teaching to the individual was ideal in the more open style of the late 1960s onwards. When the radical educationalist Tom Hudson was appointed director of studies in 1964, Joan became effectively his second-in-command. She was head of the Foundation department until her retirement in 1983.

Warm and Cool, c.1960, oil on canvas, 61x50cm, University of South Wales

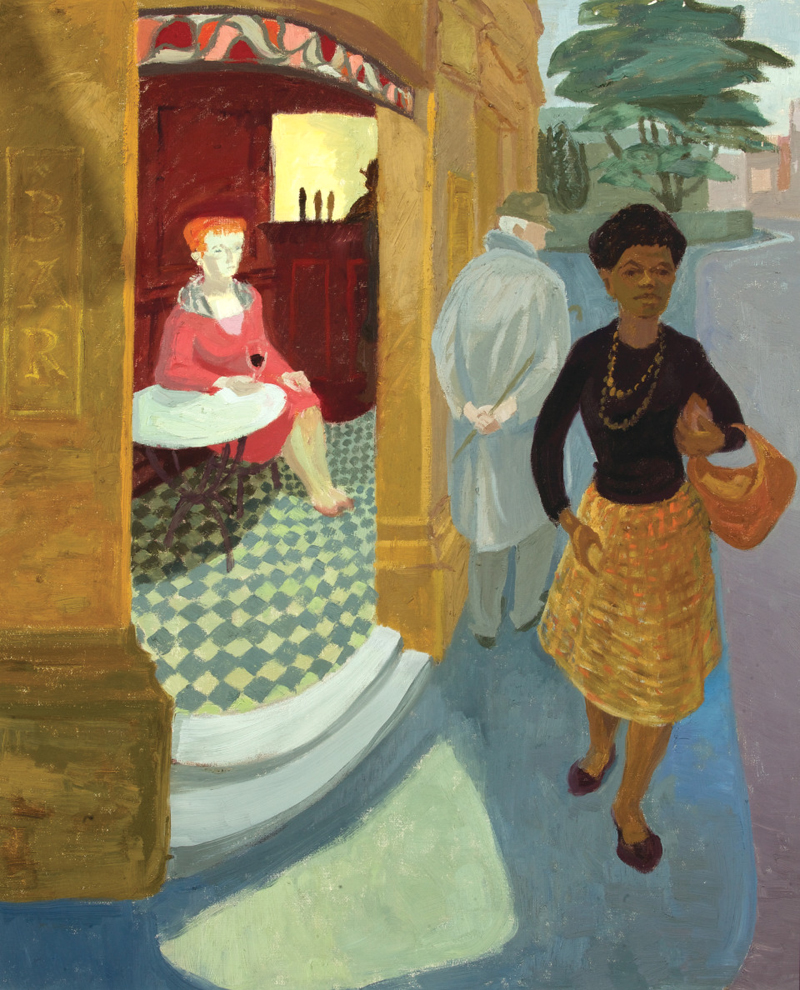

That was the public side of her professional life. The private side was her painting. In the 1940s and 1950s she exhibited one or two pictures at a time in open exhibitions such as those of the South Wales Group. Many of them were insightful depictions of ordinary life in south Wales – a prostitute working from a city bar, women in a farmhouse kitchen, her father feeding birds in the snow. Spring Evening, which showed people returning from work on Western Avenue, was the first purchase for the Welsh Arts Council collection, in 1951.

After about 1960 she left behind the realist paintings she had done until then in favour of perfectly balanced landscapes of gardens and countryside that she knew intimately, especially in Victoria Park and the Vale of Glamorgan. The paintings were almost completely without people, though many gave cameos to her West Highland terriers. These canvases were stacked up in her studio and few were ever shown, apart from in a solo exhibition marking her retirement from the art school. Why did her subjects and her attitude to exhibiting change? Perhaps it was her growing responsibilities at the art school, perhaps the dominance of abstraction and conceptual art, which inhibited many a representationally inclined painter at the time. But her paintings were fresh, beautiful and honest to the places that she loved. She said she always sought ‘to realise the ground beneath my feet and the sky above my head and all that happens in between’.

St Fagans Woods, 1991, oil on canvas, 61x76cm, University of South Wales

She continued living in the house where she had been born. In old age, still pin-sharp of perception, single, slim, sprightly in tweed skirts, she might have made a fine Miss Marple. The 1990s saw the beginning of new appreciation of her work. When Spring Evening was brought out of store for the Welsh Group’s fiftieth anniversary exhibition at the National Museum in 1998 many people were moved to tell Joan in person how much they admired her vision. A retrospective was curated by Ceri Thomas at the University of South Wales and the National Library of Wales in 2009-10. Last year she was included in Peter Lord’s perspective on Welsh art history from 1400 to 1990, The Tradition, and the special exhibition of the National Eisteddfod of Wales, Ffiniau, placed her early works alongside those of three contemporaries. She came by motorised wheelchair to the Maes, where she enjoyed seeing her old paintings and a new audience discovering them. The exhibition went on to be visited by over 35,000 people.

Joan Elizabeth Baker, artist and teacher, born 4 December 1922, died 7 April 2017

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

Peter Wakelin is an independent writer and curator. His new book, Roger Cecil: A Secret Artist (Sansom), accompanies an exhibition at MOMA Machynlleth until 24 June 2017

If you liked this you may also like:

Nantgaredig v Sweden

An image essay by Mathew Browne.

One of the Greatest Political Con-Tricks of the Modern Age

Mick Antoniw AM argues that this is the most important ballot since 1945, and warns of the devastating implications of a Conservative win for constitutional stability, parliamentary democracy and the rule of law itself.

Women at a Cliff Edge

A conversation between the author and her daughter about ‘Gwawr’, a short story in Planet 224. The story is set in the ninth century and follows a woman’s experience of the incursion of Norsemen into her community. This was the time of Viking raids along the south Wales coast.

Lies, Damned Lies and Politics: a media column

by Mike Parker.

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…