The Paper Trail 01.08.15

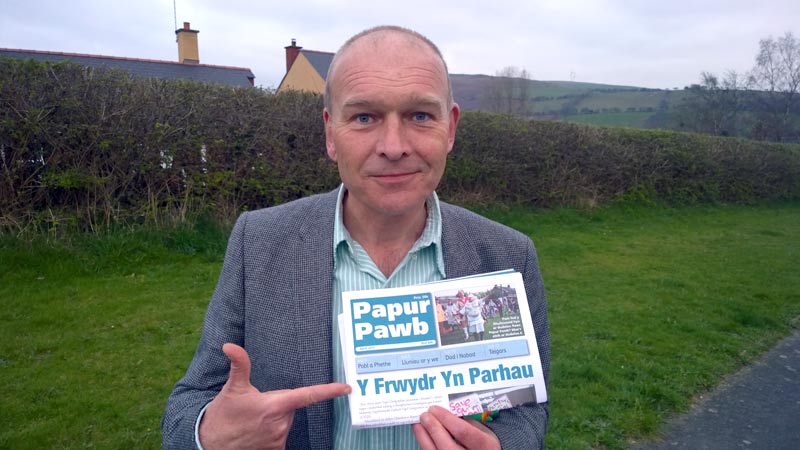

The Battle Continues: Mike Parker holding up Papur Pawb © Dafydd Prys

Mike Parker gives his account of the controversial Cambrian News distortion of his 2001 article in Planet, and is troubled by what this episode tells us about the media and the politics of race today.

‘No writer can really into go into politics, for they quite literally have a paper trail.’ The silky drawl sliding from my car radio is that of Michael Ignatieff, author and one time regular BBC pundit who was lured back to his native Canada in the early part of this century to become a Liberal MP. Within three years, he was leader of the party, taking it to disastrous defeat in the 2011 general election, when they lost well over half of their seats, Ignatieff’s included, and their status as the official opposition. He bowed out of politics just as swiftly as he had jumped in.

He ruefully calls his brief political career ‘hubris’ and ‘self-deception’, particularly for thinking that difficult topics he had written about long before would be treated considerately in the harsh glare of politics. His words sizzle into my brain. After all, I’m on the road to yet another political meeting in a distant corner of Ceredigion, where I’m standing as the Plaid Cymru candidate for the 2015 general election. I’ve been scratching a living as a writer for over twenty years. I have a very long paper trail.

Six months earlier, in June 2013, at the first campaign meeting after my selection, I’d asked everyone to prepare what they thought were likely to be the pros and cons in the eyes of the electorate of both me as the Plaid candidate, and my main opponent, the incumbent Liberal Democrat MP. Fully expecting a rigorous inquisition about my writing, instead the only three drawbacks identified about me are ‘the gay thing’, as it is decorously put, that I live just over the county border and the fact that I have an ear-ring. Strangely enough, the only male MP thus far to have one was Simon Thomas, Plaid member for Ceredigion until 2005, when the seat was lost to the LibDems. The memory of his ear-ring still seems to haunt many. ‘What about my writing?’ I ask. ‘It’s not all been the Rough Guide to Wales, you know.’ ‘Oh, don’t worry,’ I’m told, ‘it’ll be fine.’

Of course, it’s not. Four weeks before polling day, the Cambrian News, the weekly paper for much of mid and west Wales, exhumed a fourteen-year-old article of mine in Planet about the ‘white flight’ phenomenon of incomers into rural Wales. My piece had focused especially on the high command of the racist British National Party (BNP), many of whom had decamped to Montgomeryshire in order, in the words of their leader Nick Griffin, ‘to escape multicultural Britain’. Although they have now imploded, the BNP were on the march at the time; they were shortly to get a few dozen councillors elected, and then a couple of MEPs. In Dyffryn Banwy that summer, they organised a festival whose guest of honour was veteran French fascist Jean-Marie Le Pen.

Such reasons for moving were not just the preserve of paid-up BNP thugs. I was a fairly new arrival in Wales myself at the time, and had been startled by how readily some fellow incomers had told me that they’d moved here principally to get away from the multiculturalism of English cities. That they were now the in-migrants into a different culture was an irony that didn’t trouble them. It was a phenomenon that bewildered me, and I wanted to research and write about it.

With staggering chutzpah, the Cambrian News managed to turn this into different front page banner headlines on all four editions across Ceredigion: typical was ‘Incomers are ‘Nazis’, says would-be MP’, with the subhead ‘Plaid candidate defends criticism of English’. All four headlines used the word ‘Nazi’, though it was nowhere in my 2001 article. The BBC enthusiastically deployed it too, as did nearly all UK newspapers and online news outlets.

The reaction was instant and overwhelming. Social media exploded, radio phone-ins and TV debates combusted with fury, and politicians of all parties lined up to demand my sacking. ‘He must go: a racist leopard never changes its spots,’ sneered Conservative AM Byron Davies on ITV Wales’ Sharp End; he is now MP for Gower. Peter Hain, who has traded so much on his anti-apartheid roots in South Africa, tweeted that ‘Plaid Cymru must sack candidate after this ‘Nazi’ attack on English constituents’. Further distortions only threw more petrol on the flames. When challenged on Twitter, the Cambrian News journalist who wrote the original story justified it by claiming that I had ‘labelled a third of the county racist’.

Within 24 hours of the Cambrian News first hitting the shops however, a massive backlash was thundering towards them. People – and not just Plaid sympathisers – were disgusted at the chasm between hyperbolic headlines and actual story, together with the calculated misuse of the word-bomb ‘Nazi’. I received over 5,000 supportive messages from Ceredigion and far beyond, blogs and articles sprung up in my defence, the paper was inundated with calls and letters of protest, some of their advertisers took to Facebook to discuss a boycott, and the politicians and journalists so keen to put the boot in began deleting their over-eager tweeting. Even Alastair Campbell, Tony Blair’s spinmeister, retracted his initial outrage and admitted that he was ‘misled by paper and Twitter reaction’.

Of course, any newspaper is entirely free to pursue its own political agenda, and the Cambrian News has never made much secret of it. It was founded in 1860 explicitly to support the Liberals; it has done so pretty much ever since. The week after the Liberal Democrats shock defeat of Plaid Cymru in 2005, the paper’s editorial praised the new MP and the ‘laudable goals’ of his party, and gushed that ‘there is probably one man, now seated in the great debating chamber in the sky, who is nonetheless delighted with the win, Mr Williams’ predecessor Lord Geraint of Ponterwyd. Let us hope that Mr Williams can follow in his revered footsteps.’

Within this context, such loaded front pages were perhaps no great surprise. The BBC however is a different story. They helped propagate the central falsehood more than any other media organisation, and that is of enormous concern.

Assorted materials from Mike Parker's campaign © Mike Parker

If we look at their election coverage throughout the campaign, my little dust-storm fits squarely into the BBC’s persistent ‘nasty Nats’ narrative. Days passed in hysterical and exhaustive contemplation of what Nicola Sturgeon had or hadn’t said to the French ambassador, a ridiculous non-story that was subsequently revealed to be a LibDem leak. In the final two weeks, when the full force of anti-Scottish sentiment was being stirred to great effect in England and Wales, BBC news took to showing any couple of Glaswegian neds hollering at Jim Murphy as the main story of the day. I only wish their cameras had been around when I had people spitting at me in the street and screaming into my face that I was a ‘fucking Nazi’.

The LibDems held on to Ceredigion, with a majority over Plaid down from nearly 8,500 in 2010 to just over 3,000. It’s impossible to know how much of an effect ‘Nazigate’ had on the result. Numerous people told me that the baseness of the smear, and the way in which it was handled, actually made them decide to vote for me, but doubtless it put many others off. Right up to election day, it was an issue that never went away.

Even with quarter of a century’s inside experience of the media, the whole episode startled me, and not just for obvious personal reasons. I’d never before truly appreciated the transcendent power of lurid headlines; one that far, far outweighs any actual content. In lieu of any legal redress (the extreme time pressures of an election campaign mitigated against that), we demanded and obtained a right of reply in the Cambrian News, which appeared a fortnight later, tucked away on an inside page. Few people noticed it, and it made negligible impact compared with the open wound of the initial headlines.

There are two particularly unhappy elements that linger from this for me. The first is how the issue of rapidly changing demography, without question one of the hottest in rural Wales and one that impacts on all policy areas from health to housing, education to language, is tiptoed around as if it is an unexploded bomb. Our reluctance to engage honestly with what is happening is only fuelling problems and prejudice in already beleaguered communities.

The other (and it is of course related) is how far and fast our discourse on racial issues has gone downhill since 2001. My original piece in Planet provoked some press attention at the time, though it was far more considered and contextualised than anything said about it this time round. Reports on what I’d written hit the front pages of both The Guardian and the Daily Telegraph on 10 September, 2001.

The following day of course, the world changed for ever, and crude racism began its creep from the shadows into the mainstream of political and media discourse. The BNP, whose rise so alarmed me in 2001, may be dead, but most of its loyalists, Nick Griffin included, have declared that they’re now UKIP voters. Language around migration and race has become coarsely reductive in ways that would not have been acceptable even at the turn of the century. And in a truly Orwellian twist, it is now turned to mean its precise opposite; the anti-racist becomes the racist, and the ideal object for that day’s Two Minutes Hate.

About the author

Mike Parker is the author of Neighbours from Hell?, The Map Addict, Wild Rover, Mapping the Roads and others, and he is currently working on a political diary.

If you liked this you may also like:

Careful Headlines

Dafydd Prys on the power at the top of an article.

Pride: review

Mike Parker reviews the film Pride. Set in 1984 during the Miner's Strike, the London Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners group joins the strikers of Dulais; you are challenged no to be moved.

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…