Mr Jones: Not the Only Gareth Jones

A Film Review by Ned Thomas

Ned Thomas draws on his archival research into the extraordinary story of the Welsh journalist Gareth Jones, his work on George Orwell and his experience working in the USSR to give an in-depth review of the new film Mr Jones ̶ an exploration of the ideological conflict surrounding the famine in 1930s Ukraine.

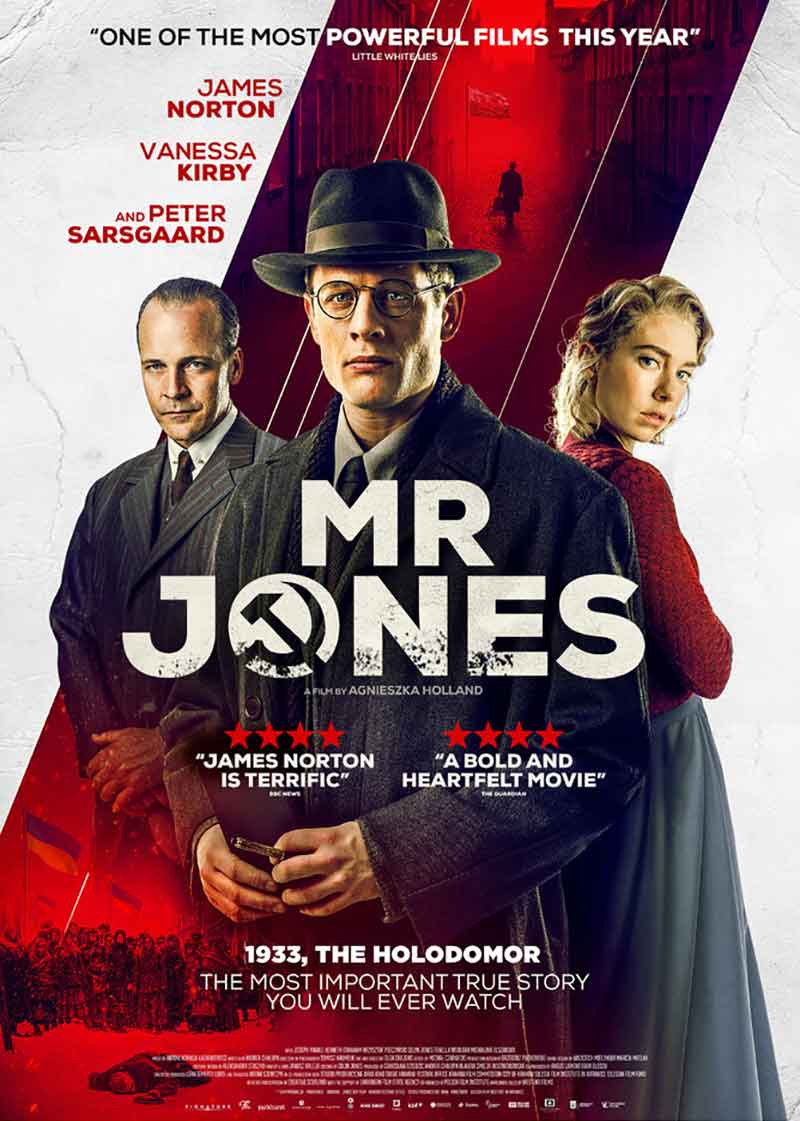

Film poster for UK release © Signature Entertainment

Last week (February 7) saw the UK launch of Mr Jones, a feature film which in other language-versions and at film festivals has already carried the fame of Gareth Jones to wide audiences. Many Planet readers will know his story if only in outline: a young Welsh journalist and researcher to Lloyd George visits the Soviet Union and writes one of the few eyewitness accounts by outsiders of the great famine of 1932/33 which resulted in deaths estimated at anything between three and ten million people. His account is rubbished by well-known foreign correspondents based in Moscow at the time, whether for ideological reasons or mere self-interest, whether manipulated or bribed by the Soviet authorities. In 1935, when not yet thirty years old and on another news-gathering mission, Gareth Jones is murdered by bandits in Manchuria. While this was possibly, even probably, at the instigation of the Soviet secret services, this is stated as a fact in the final credits to the newly released film.

The film was originally to be called Gareth Jones which is how he is known and revered as a national hero in present-day Ukraine, and that of course is how we know him in Wales. That shift of title can alert us to what is going on. Gareth Jones as ‘Mr Jones’ is being turned into an emblematic figure – an unknown but decent chap from the periphery who through the connection with Lloyd George wanders into the higher circles and centres of international politics, insists on making public what he has seen with his own eyes, and pays the price.

By the end of this review you will find that I have qualified my praise, so let me say at the start: James Norton as Gareth Jones is an admirable performance and really carries the whole film. He conveys an inwardness and a kind of innate puritanism and moral sense co-existing with sharp intelligence, warmth and humour which I found wholly credible given Gareth Jones's background in an intellectual, non-conformist Welsh-speaking family at that time. One has come to fear the worst in terms of stereotyping when Welsh characters appear in films made elsewhere. The multilingual nature of this Poland, Ukraine, UK co-production and the history of the Welsh and Ukrainian languages must have sensitised the whole operation. There are snatches of credible Welsh as well as Russian in the film. Gareth Jones was a linguist and fluent in German, French and of course Russian, which meant that he could speak to ordinary people, unlike most Moscow correspondents then – or indeed later on. When I spent an academic year in Moscow thirty-five years after Gareth Jones, representatives of the English-language press still met in the bar of the Metropole and with one exception had no knowledge of Russian, making them dependent on official sources (and sometimes official sources posing as unofficial ones).

In the service of the central point which the film is concerned to make about commitment to the truth and the duty to expose atrocities, it is prepared both to depart from and add to the actual experiences recorded by Gareth Jones. Gareth Jones carried no camera but in the film he is a photo-journalist, which is anachronistic. It is now well-established that the famine led to many cases of cannibalism in Ukraine, but there is nothing in Gareth Jones's notebooks and letters in the National Library at Aberystwyth to suggest that he experienced or even heard of these, yet in the film he eats human flesh. One can argue that this element is introduced in the service of telling the truth about the famine more comprehensively. George Orwell and Animal Farm figure large in Mr Jones, and it is true that Orwell and Jones shared the same literary agent (who in the film brings them together).

But Animal Farm comes nearly ten years after Jones's death, by which time many other factors had helped shape Orwell's view of the USSR. And in 1936 Orwell reviewed a very relevant book by a Moscow correspondent which describes the ganging up against Jones, yet Orwell does not mention this in his review so I very much doubt that they knew each other. Yet there is a sense in which the two have parallel experiences.When Orwell completed Animal Farm he at first had difficulty in finding a publisher because of the pro-Soviet feeling in Britain at the end of the Second World War, just as Jones in his time found himself squeezed out of progressive publications because of their sympathy with the new Communist regime at a time of great unemployment in the West. Finally there is the question of what is present in the notebooks but not in the film. Although he does not visit the nomadic Kazakhs, Gareth Jones reports that they too are dying of hunger – in fact a higher proportion of their population was lost than in Ukraine. While a reading of the notebooks can take one in several directions, the focus of Mr Jones is quite sharply on his trip to Ukraine rather than on the wider Soviet or global context, which is unsurprising given that the film is co-financed by Polish and Ukrainian state funding organisations. In theory all the departures from the Gareth Jones documents are covered by the claim that the film is merely ‘inspired by’ his life, which is fine for those who are able to measure it against the documentation or other treatments of the subject-matter. But for many others Mr Jones may become the only Gareth Jones they encounter, and that thought makes me uneasy.

Those who want a documentary should visit or revisit the excellent Hitler, Stalin and Mr Jones made for television by George Carey and Teresa Cherfas in 2012. This both sticks closely to a variety of sources including Gareth Jones and at the same time places the action in a global political perspective. It was followed up in a Planet article by Teresa Cherfas which led to an interesting debate with Gareth Jones's American biographer Ray Gamache about whether Gareth Jones held or didn’t hold certain sympathies (or at least ambiguous feelings) towards Nazi Germany. Documentaries may stick to facts which feature films can ignore or enhance, but documentaries too are inevitably a selection and an arrangement of facts, a constructed narrative, and no account of the famine of 1932/33 is uncontroversial. Живи (The Living), filmed in Ukrainian with English subtitles, consists of interviews with survivors, children at the time of the famine and in their late eighties or nineties when interviewed. Because the interviewees have been allowed to speak at length with minimal editing, they bear witness to the famine but at the same time include elements which problematise it. Who were the enforcers at local level? Who had the privilege of ration cards which gave access to food? ‘Our own people’ says one old lady.

Ned Thomas will give a presentation on Gareth Jones at 7pm Thursday 13th February 2020 in Aberystwyth Arts Centre cinema before a showing of Mr Jones.

- 1: Mr Jones (dir. Agnieszka Holland) now sceening in UK. Soon available on DVD

- 2: Hitler, Stalin and Mr Jones (dir. George Carey, producer Teresa Cherfas) 2012 now on YouTube.

- 3: See also Planet 210 and 211 (Summer and Autumn 2013) for article by Teresa Cherfas (‘Germany, my Beloved Land’) and correspondence with Ray Gamache.

- 4: Живи (The Living) (dir. Sergei Bukovsky) 2013, now on YouTube.

- 5: See Ned Thomas's article in O'r Pedwar Gwynt, (‘Gareth Jones a newyn Wcráin’), Winter 2018 (https://pedwargwynt.cymru/adolygu/gol/gareth-jones-y-llyfrau-y-ffilmiau-y-propaganda).

This review was amended on 14.02.20 to remove a reference to an orgy in the film occuring in the Metropole. The orgy depicted in the film instead occurred in Walter Duranty's flat.

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

“Since its inception almost half a century ago, Planet has consistently pushed our boundaries of discourse. It has challenged, provoked and inspired, and always remained true to its own subhead (‘The Welsh Internationalist’) by placing our small country in far wider contexts. In a world where so many are hell-bent on building barriers and narrowing horizons, we need it now more than ever.” - Mike Parker, author.

You can contribute to Planet's future following successive cuts to our funding by taking out a Supporters' Subscription. Our new Supporters’ Subscription packages include a range of exclusive products, benefits and reading experiences drawing on nearly 50 years of Planet's history. For more information please click here.

About the author

In a varied career as writer and journalist, academic and publisher, Ned Thomas has worked in London, Paris, Salamanca, Moscow and Wales. He is the founding editor of Planet, and is known as the author of The Welsh Extremist (1971), and more recently, Bydoedd: Cofiant Cyfnod (2011), which won the 2011 Welsh Book of the Year award.

If you liked this you may also like:

Cymru, yes?

In the lead up to the General Election, poet Patrick Jones gives the case for why independence for Wales is the only way out of our current malaise of austerity, hopelessness and xenophobia, and celebrates the people and historical movements that have inspired his stance.

Planet Video: Blacklisted

In 2013, The Dragon Has Two Tongues director Colin Thomas wrote an article for Planet entitled ‘From Blacklist to Oscar Shortlist: Paul Turner, MI5 and the BBC’ on how the career of Hedd Wyn director Paul Turner had been affected by political blacklisting within the BBC, and examined whether blacklisting continues to blight the UK media.

Planet at 50: A Celebratory Event Hosted by the National Library of Wales

In 2020, Planet celebrated 50 years as Wales' liveliest cultural and political periodical. Watch this video of founding editor Ned Thomas and current editor Emily Trahair in conversation with author Mike Parker at this event from December 2020 to see what's changed, what hasn't, and why a publication subtitled 'The Welsh Internationalist' is needed now more than ever