The Poet, The Donkey and the Quandary 25.05.14

Sion Tomos Owen describes how his passion for politics was shaped by the course of the global recession and his experience of unemployment.

Congratulations to Sion Tomos Owen, the winner of our 2014 Essay Competition 'Wales in Hard Times' (young writers' prize), which invited creative responses to the economic crisis in post-devolution Wales. David Greenslade won the general writers' prize. We would like to extend our thanks to the National Union of Journalists for so generously sponsoring our competition.

At the time of the 2010 UK elections, in the immediate aftermath of a recession, I was a poet. The manufacturing company I had worked at for almost two years went into administration and I was made redundant, after which I settled on ‘Poet’ rather than calling myself ‘unemployed’ or ‘between jobs’. If my sixteen-year-old artistically-minded self had seen me in my previous job, sitting in an office, studying tenders and punching numbers into a computer spreadsheet he would have sharpened his paint brush and committed harakiri. It wasn’t a job that I was particularly fond of but one that I learned a great deal from. I had mainly worked in shops, warehouses and building sites, and the replacement of site banter with office politics was an eye-opener, a fist-clencher and back-stabber. It was an average March morning when a stream of dark-suited men stormed into the office unannounced and told us to close everything down. After two days in administrative limbo I was freed from my desk job to explore other avenues of employment. As the weeks wore on, those avenues increasingly became marked with ‘No entry’ signs. The eminent Rhondda author, Gwyn Thomas, wrote that, ‘The beauty is in the walking – we are betrayed by destinations.’ How right he was about the months to follow. The destinations were definitely betraying me, but the walking...

To add routine to the monotony of an unemployed day, I began reading the papers thoroughly. Weeks turned into months of applying for any job from window cleaner to media worker (telesales) and hearing nothing back. I was a frustrated ‘over-skilled’, underemployed advert for Generation Y. A generation of algae on the surface of a reservoir of promised opportunity that was being dredged by the recession. So, as my grandfathers did in such times in the workmen’s halls and libraries that they had built for themselves, I began to educate myself. I read the Western Mail that my parents had delivered to the house, then The Guardian online. I’d fetch the Independent from the newsagents, read The Week and Prospect in the library – anything I could get my hands on. I was devouring current affairs faster than a politician could avoid a question, and I slowly began to learn how and why they did it too.

I hadn't been particularly politically minded until this point, but my father had always said, given the right circumstances, I would eventually become so. However, at university I had been on marches over rising student fees and my picture had turned up on a website declaring me a ‘Red Socialist’, which I only later found out was meant to be an insult. Coming from an ex-coal mining valley community, the ideological implications of socialism were ingrained in me, but the concept of socialism as something to fear or avoid was something alien that had to be explained to me by an American Studies lecturer. I was perplexed by how it could be viewed as a bad thing until he explained that these views were historically driven by socialism’s links to America’s complicated and fantastical relationship with communist countries, and the negative connotations socialism had in thwarting ‘democracy’ and, inevitably, the true American Dream of capitalism. It was a revelation of the wider world to an intrigued Valley boy.

By April 2010, the 3-way televised election debates were underway. I was pretty clued up on what primary colour the party leaders were as well as which yarn each one was spinning: Anti-Blairite, Post-Thatcherite, Neo-Gladstonite. These debates would prove the tipping point for the Liberal Democrats and echo in the dawn of Cleggmania. This was the phrase coined by the media after the public’s hope swelled on seeing a political leader who seemed to offer something new: honesty. Polls screamed that we’d vote in hordes for the new Messiah (only 23% voted with actual ballot papers, not superlatives), yet it took less than a year to discover that yellow-tie man was just another very naughty boy and the novelty of his honest approach was merely neo-bullshitism.

By this point I had also watched Series Three of The Wire. This is the ‘Politics’ series and follows the Mayoral Campaign of Tommy Carcetti as the social background to the ongoing drug-running turf wars on the streets of Baltimore. I’m not ashamed to say that I learned and understood more about the intricacies of politics from those 14 episodes than in all the articles, columns and Oxford Short Introductions I’d read trying to understand it.

My poetry became fuelled by my new-found interest in the ever-present issue of politics, and I had found a platform on Facebook and Twitter which served to start debates, rather than simply being the experience of scrolling 50 photos of old school friends’ new babies, or statuses washing dirty laundry in public. I had folders (physical and digital) full of social commentary poems and an iPod full of political podcasts. I was immersed in and riveted by it all.

Conservatives to reopen mines: A dialogue

'Reopen the mines!

(For out of sight out of mind)

Numb our oldest feud.'

'Unclose the mines.

This valley’s made for churning

Our souls for the flue.'

'Re-export the coal.

Striking into the earth’s core.

Fibres of your being.'

'Re-expose the cuts.

Blue veins black. Comrades of dust,

In darkness, living.'

'Revisit the face.

Fire up enthusiasms:

The furnace of change'

'Envisage our face.

Fire and pick and white eyed.

Black marks on a page.'

The power to rule the people inevitably corrupts politicians worldwide.The only difference is that in democratically elected nations, which uphold the Western Utopia of Governance that we so wish to impose on the rest of the world, the corruption is far more discreet. It’s managed, polished, repackaged, ingested and repeated so that all we are left with is the old adage: ‘All politicians are liars and are all in it for themselves,’ and we simply leave it at that.

When I first voted in the local elections in 2004, after turning nineteen, when I had yet to immerse myself in politics, I voted for the only person on the ballot that I had heard of. I knew him, I knew he was local to the area and I knew he was a good man. I would see him walking around town, I would speak to him and later he would tutor me during my A-Levels. It just so happened that he was the ward member for Plaid Cymru. That year they retained the Treorchy ward and so I assumed that I had made the right call based on the collective vote of my community.

Four years later I was a student at Trinity College Carmarthen, and out of discord with the war in Iraq, a number of my friends voted for the Liberal Democrats (stereotypically, the Lib-Dems being the so-called left-leaning voice of the student). Since I had no idea who the candidates were, I voted Plaid again purely on the basis that I felt I had voted ‘correctly’ the previous time. They also won in Carmarthen. It seems I was on a roll.

When I returned home, while speaking to some older voters in a Brachi’s cafe about the election, I mentioned how I had voted. They were appalled at my reasoning. What I deemed a logical extension of my naive political apathy enraged them. Why hadn’t I taken into account any current affairs or read up on anything before casting my vote? I was considered a brazen fool for even mentioning it to them.

At the time I simply took it on the chin. Then I asked them who they voted for and why. Almost all replied ‘Labour’ and I noted it as my first encounter with party differences. What I assumed would be a simple exchange became much more confusing, and what followed stymied a genuine political discussion: ‘My father voted Labour and his father and his before that and I always will, don’t matter who the guy is.’

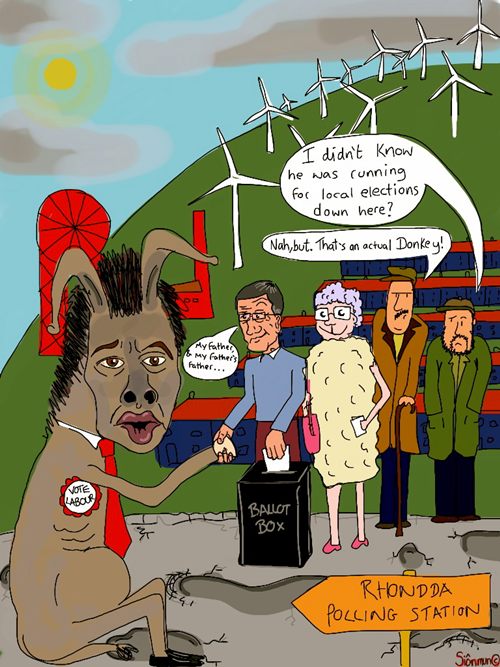

This wouldn’t be the last time I’d hear this. But it started to make me question things about my beloved valley and its people that I hadn’t before. The old joke that if you pinned a red lapel on a donkey in the Rhondda, people would vote for it, was actually true! Strong, opinionated people who stood up for what was right no matter who the oppressor was, began to seem like... sheep. I couldn’t handle another stereotype.

By 2010, the shitstorm that was the global economic crisis was raging, the lies about WMDs in Iraq had been exposed, Brown had replaced Blair as Prime Minister and politicians had been exposed for exploiting their expenses. Even the most fervent member of the Labour Party, I thought, must have been questioning their government. Now armed with understanding on the subjects along with my own informed views, I could actually hold discussions and debates with those people who had berated my choices last time around.

I was now in a quandary as to my own political leanings from information overload and discussions with canvassers. I believed I needed to make an informed choice and so needed this platform to hash out the pros and cons, the local and national debates that I assumed took place in the pubs and clubs during elections. But, alas, where I believed a new dialogue could be forged from the flames of five years of controversies and economic collapse, opinions remained bafflingly stagnant.

I was again chastised by the Brachis regulars for questioning their resolve. They saw it as political heritage whereas I saw it as nostalgic ignorance. The ‘issues’ would not cloud their judgment. There are two options: Labour or Conservative. Red or Blue, it was black and white to them. I mentioned the Lib Dems or Plaid Cymru, but they assured me that locally or nationally there was no grey area. Where I saw a rainbow of options they saw two opposing ends. I was confused by the simplicity of their argument and gutted by what I saw as bigotry in my fellow comrades.

What made things worse was that I was made to feel the naive fool, again, come election day, as I was ensconced by the middle ground. On telly the posh boy and the old guard exchanged repeated barbs of yore as the pale new rider who spoke of clarity and change convinced my mark upon the ballot.

I voted Lib Dem.

But all it took was five days of rolling news for me to regret my decision. It took even less time for those I considered foolish with antiquated views to don their armour and lay into me for what seemed to them to be geo-political treason: ‘Look what you’ve gone and done now! You with your bloody hippy views to try to change things and look what’s bloody happened!’

I genuinely felt to blame, since I truly believed I could skew the pendulum, change the platform, but all I did was play into the hands of my Labour-voting neighbours for argument’s sake. Where I thought they were cutting off their noses to spite their faces, what they were actually doing was making sure the scars were visible. But these scars were not new, as I would learn from the death of an old woman a few years later.

On 8 April 2013, Margaret Thatcher died. I then saw first hand what I struggled to comprehend during those early experiences of drawing party lines and fathoming political ideals. I knew ‘that woman’ was not a friend of these parts and that many considered her the enemy. But being born the same year as the great miners’ strike I was told by ‘moderates’ that I ‘had no right’ to voice my disapproving opinions of her since I was ‘far too young to remember’ let alone understand those times. However, I then realised that the arguments of ‘Thatcher’s Children’ here in the Rhondda are based on an ideology rather than being the uneducated opinions of those too young to witness her policies. Furthermore, I may not have understood what was happening at the time but I can now see and understand what has happened since.

The economic scars left here are still fresh. There isn’t a single mine open (Maerdy was the last to close in 1990), very few factories are left (Burberry’s closed in 2007), and we haemorrhage down the railway line to Cardiff more and more to work in call centres: the mineshafts of the age. Nothing is made here anymore. We fuelled the world and now we are the burned-out embers of a forgotten industry which has been replaced by derelict chimney stacks, rusting trams on motor cross-gouged tips, and crumbling factory warehouses where I used to aim to smash the glass on the top floor windows. Oh, the shattering of metaphorical irony.

Walking past the old EMI factory in Treorchy, which has stood ruined for almost a decade now, the level of economic desperation and need hits home. There are plans to open a new Tesco on this site. Plans that have been in the pipeline for years but have come up against opposition. It may ruin the nature of the town and will definitely create traffic congestion but it would also fill a gaping chasm of youth unemployment in the area.

Those Labour stalwarts were not so because they were driven by Blair, Brown or Miliband’s policies but rather they were opposed to returning to a time where they were driven by Thatcher’s. The political landscape has changed radically, metamorphosed into a situation where politicians are not only the governors of the land but are the celebrities of television, radio, Facebook and Twitter. With even more ways to connect to the electorate, modern politicians seem so far away from the times when my sparring partners’ opinions were formed. There is a fear and an anger and a sense of hopelessness that permeates through their staunch dedication to their party. They’ve lived through a time where everything changed, and the phrase ‘those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it’ remains fresh. Thankfully this ideology remains ingrained in some, who are impassioned enough to voice those opinions and not be quelled by the ‘respect the dead’ nonsense spouted on social media as a way of dampening free speech. A frail old woman she may have been, but in 2013 Thatcher was staying at The Ritz, London, surrounded by luxury, as we suffer austerity and hardship, surrounded by the remnants of a dying community, industry and society.

What I'm still learning is that come the next election there may be a bitter pill to swallow if I am to truly understand how politics works around here and how it genuinely affects us as a valley, a county and a country. Yet the grand irony of all this is that during these quarrelsome, grassroots debates in the heart of the south Wales Valleys, the Welsh Assembly is hardly ever mentioned.

We feature further reviews and analysis in the magazine. See our contents pages in the archives section and you can buy issues here.

About the author

Sion Tomos Owen is a poet and short story writer.

If you liked this you may also like:

A Native Alternative

Frustrated by traditional Welsh-language culture Miriam Elin Jones explores new debates about ‘Welsh futurism’ in music and literature.

Athens Refugees

Catrin Stewart reports on what she saw when she volunteered with aid organisations working in the Greek capital city, Athens, providing support for refugees.

A protest in Powys

Tim Holmes explains why he set off an alarm at the Powys County Council budget meeting