Reinventing the Familiar

PICASSO Challenging the Past. National Gallery, London.

25th February – 7th June 2009.

Sponsored by Credit Suisse

Present economic realities not unnoted in the introductory words from Eric Varvel, CEO Middle East, Europe and Africa.

This exhibition, curated by Christopher Riopelle and Anne Robbins of the National Gallery, aims to demonstrate Picasso’s debt to the past and to show how he confronted the work of artists, initially those of Spanish origin, whom he considered masters in their particular genre, and whose accepted brilliance offered an obstruction or challenge to the claims of his own genius. It provides an intense and revealing experience, setting out the evidence in a series of galleries dedicated to a variety of themes that are illustrative of most aspects and periods of Picasso’s long, productive and very public career.

Aspects of Picasso’s work on show at the National Gallery have a familiar feel. Beginning with the years of the first art schools, up to and beyond the advent of Abstract Expressionism, an essential part of the education of the painter was the study of the old masters, the established greats. It was believed that the most effective way of understanding the complexity of composition — colour, tone, harmony, discord and all that made a work of art successful — was by making a transcription. This entailed the close analysis of a painting, considering scale, colour, content and shape, as well as the abstract and compositional elements upon which the work was based. A thorough engagement with transcription is a vital part of a musical education, familiar to those who learn the piano and other instruments and an essential element in the development of jazz and modern music.

It is strange, therefore, that in none of the many reviews I read was there any mention of the tradition of transcription in the visual arts. Even today in the National Gallery one sees artists and students working from the great masters. There is a long established and ongoing residency programme where prominent contemporary artists engage in responses to work hanging in the galleries. However, few established artists continue with, and develop, transcription as an essential part of their mature work, as did Picasso.

“Disciples be damned… It’s only the masters that matter. Those who create…” is, of course, how Picasso famously dismissed the followers of the old masters. This somewhat hubristic statement reflects his unease, his uncertainty, as to his own position in a pantheon where absolutes are largely a matter of fluctuating opinion. He certainly saw himself as a master from early in his life, superior to his contemporary rivals, and even his famous predecessors. His father, a reasonably well-established painter had handed his own brushes over to the thirteen-year-old Picasso, in recognition of his precocious talent, and this phenomenal facility was something he battled against all his life. Having usurped his father, his mother continued to haunt him, and it was to her his subsequent efforts as an artist were largely addressed, even if unconsciously. Gertrude Stein observed that Picasso was beholden to the powerful matriarch who dominated the family, and felt that Picasso’s subsequent battles with the female form reflected his fear of and desire to appease his mother.

The exhibition shows his working from the well-known paintings of other artists, established painters whose iconic status he sought to emulate and whose subject matter echoed some of his own thematic obsessions. Perhaps they conveniently offered a ready starting point when he felt his own imaginative powers beginning to flag. What Picasso does in much of this exhibition, is, quite simply, transcription; he examines, dissects, deconstructs and reassembles in a new and personal way work and themes that hold a particular fascination for him. The carefully laid out exhibition gives the viewer a snapshot of his career in a judiciously constructed trajectory, running from his early years, through his many stylistic variations, up to the period prior to his death in 1973.

Beautifully arranged, the thematic hang allows the curators to vault chronology and to combine work from differing periods in the artist’s career.

The paintings are laid out in six galleries containing contemplative groups, each of which becomes a complete exhibition in itself, thus creating a narrative rather like the chapters of a book, offering conversations between paintings from the various periods of his life. However, the catalogue disappoints. It is written as a series of seven essays on Picasso’s life and work by the curators and other specialists, and although valuable in itself and intelligently supporting the curators’ ideas and theories, it is oddly written in parts, and of very little interpretive help as it does not follow the order of the exhibition, and thus offers little assistance on a walk around the galleries, and complicates any subsequent reflective engagement. While the reason given for this is the desire to create a document that will be of value after the exhibition itself has faded into history, my own feeling is that the format was largely the result of the limitations placed on the curators by availability and thus a pragmatic necessity, rather than a curatorial objective. The exhibition began last year in Paris as a much larger inter-museum show, and this truncated version, welcome as it is for its sharper focus, has perhaps not been quite brave enough to be what it is, rather than what it might have been.

The exhibition begins with The Self Portrait in Room 1, and continues through galleries dedicated to Models and Muses: The Nude, Characters and Types, Models and Muses: The Pensive Sitter, Still Life, ending with Variations. The latter explores works made in response to paintings by Delacroix, Manet, Poussin and Velasquez that offered Picasso the creative possibilities of engagement with the transcriptive act.

Picasso’s most significant preoccupation with the past came rather late; he was well into his seventies when he began to paint the series of variations from those masters who had haunted his imagination. He was, however, wide open to influence, stating openly that “all art is theft”. He took from wherever he thought fit, applying this axiom very enthusiastically during his early years in Paris, where his debt to other artists was considerable. Toulouse-Lautrec became a major source of subject matter and style. While Picasso worked closely with Braque and Matisse, the influence of Cezanne was also significant, particularly after the posthumous exhibition of his watercolours, and his friend Derain’s work was discreetly exploited during those years.

The scale and hang of the exhibition, in a format which is becoming more common and a welcome relief from the crowded blockbuster, is small, intimate and not overcrowded with pictures, consisting of around sixty works, and thus allows the viewer to examine in some detail the subjects on which were brought to bear the ambitions and unrelenting gaze of the most well known of twentieth century artists. El Greco, Velasquez and Goya were the great Spanish masters from under whose shadow he sought to emerge, although an echo of the lasting legacy of the great Spanish triumvirate dominates the show in a manner that — were he around to see it — he would probably question, perhaps regret.

The exhibition begins with an 1897 painting, Self Portrait with a Wig. Worked in the style of Goya, an old face emerges from under a grey wig, the eyes black and implacable, while clearly visible underneath is the form of a previous work, not mentioned in the caption or the catalogue, but nevertheless worth looking for as it demonstrates the febrile restlessness of Picasso’s imagination from very early in his life. This image establishes the context of the exhibition, for here Picasso looks at himself, and subsequently gazes out at us the viewers. He is gone but remains staring at us, caught in time. The exhibition then begins to move through his life, through variations in media, and ambition, in style and treatment, we witness the changes that he underwent as his life progressed; his loves and lovers, his fears, joys, triumphs and disappointments.

It is astonishing that he painted this self portrait when barely sixteen years of age — there is such assurance in the handling of the paint, the drawing, and the composition and in the tonal considerations he demonstrates all the skills of the masters with whom he was striving to compete. The grey wig and the expression on the face give the head the look of a much older person and reinforces the notion that a major part of Picasso’s self was perhaps much older when he was young, grew younger as he aged, and that he died almost a child.

The self-portraits include early work from his Barcelona years, his cubist period, and the classical, surrealist, middle and late stages of his life. The variety of media used demonstrates Picasso’s prowess in turning inert material into art. His 1938 self-portrait in charcoal, The Artist in Front of his Canvas, sweeps energetically across the canvas, the charcoal’s dusty mark underlining the hollow monumentality of the mortal figure. It is a compelling mixture of the cubist, the classical and the surrealist, where the strangely feminised artist gazes into the mirror ready to begin his work. The reductive nature of the figure has led some commentators to suggest self-doubt on the part of the artist. I believe, however, that this illustrates Picasso’s desire to confound our expectations. The drawing exercises ambiguity, it has areas of redrawing, overdrawing and erasure; we can follow the line, it is simultaneously convincing and confusing in its elasticity and in its refusal to be fixed. It proclaims a premature, post-modern self-awareness, stating uncompromisingly that it is a straightforward charcoal drawing representing an artist at work and that is all; an extravagant simplicity.

In The Kiss (1969) — included among the self-portraits because it features the artist kissing, or what looks more likely, strangling a woman, possibly his wife at the time, Jacqueline Roque — we see an alarmingly violent assault by an older man on a much younger women. Much of the primitive machismo that becomes a powerful feature of his later work is complemented by what is clearly an increasing fear of the female and is said to be a response to his fears of artistic and sexual decline while the application of paint to the bodies of his female subjects in aggressive gestures reinforces the sense of his violent frustration.

In Models and Muses: Nudes, we are faced with some of Picasso’s most humane and sensitive work. The room features work from every decade of his life (apart from the 1910s), when he was largely engrossed in his cubist experimentation. The tenderness of the early work is beautifully seen in Combing the Hair (1906) with its discreetly subdued colours, careful composition and gentle holding of the hair. The three figures stare intently; engrossed in their preoccupations, the child looks down, the hairdresser examines the hair, while the subject gazes into the mirror. Nude with Joined Hands (1906) portrays Fernande Olivier, his then lover, in a pose echoing Cranach’s famous Eve. The figure burns with the hot ochres of Spanish terracotta, fingers intertwined, alone in the canvas, vulnerable and isolated, seen as if stepping out of the furnace.

The artist had spent the summer with Fernande in the Pyrenean village of Gosol. From here, he seems to have brought his early period to a final dramatic climax. On his return to Paris Picasso ignored the colourful excesses of Fauvism, which were taking up the energies of his great rivals Matisse and Derain. He looked instead to out-paint them, to create an original, even more violent break from the outré conventions of the Parisian avant-garde, and he did this by combining the Blue and Rose periods and mixing them with a revolutionary synthesis of primitive forms from Iberian and African sculpture.

That sculpture was to provide the inspiration for pictorial experimentation is something of a surprise. In a way Picasso looked away from painting, and then back, in order to take painting forward, and in so doing he took the whole cultural output of the early twentieth century into an accelerated evolutionary cycle that was to influence music, literature, cinema, dance and theatre.

Picasso drew relentlessly, he made things, he invoked a cast of characters, calling them up from a combination of acute observations and restless imaginings, and he included himself, becoming a repertory artist in his own drama as these familiar figures and motifs became his cast, the subjects and subject matter of further and more challenging explorations. Form mattered, the integrity of the painted surface, the re-invention and distortion of the familiar, the traumatic ambush of aesthetic, pictorial and perceptual expectations.

It was from Cezanne’s series of bathers merged with his Rose period figures and the new sculptural forms that Picasso created the shockingly dishevelled, the raw and alarmed-looking figures that people his extraordinary painting, Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) a painting that when finished (or more likely abandoned) could be neither shown nor sold. It became the subject of rumour, of speculation, of notoriety, and at the time most of those given the chance to view the Demoiselles were appalled by its apparent ugliness, its seeming brutality and uncompromising indifference even to radical contemporary notions of beauty. They looked away. And yet, now, it is beautiful, compellingly and extraordinarily so. Those discomforted figures look out in shock at the strange new world that was taking shape as the twentieth century took its first faltering steps.

The passage of history and his changing personal life created Picasso’s subject matter, themes and treatments, and he was always ready to steal from his own past, calling on elements of previous work as the occasion demanded. After the First World War, he began designing sets and costumes for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe, and in 1918 married Olga Koklova, a dancer with the ballet, beginning a brief period of calm, domestic portraits of his wife. In 1921 Olga gave birth to a son, Paolo, which triggered another change as Picasso’s output focused on the monumental, classically inspired nudes, idealised lovers, children, bathers and mothers nurturing infants. The painting Seated Woman (1920) is an early example of this genre, a style that has been seen as the construction of a solid, immutable world to contain the mother and the son he worshipped.

Picasso’s domestic and emotional arrangements usually very rapidly outran their initial enthusiasms and in almost every case his reaction was a complete change of agenda in his art. By the mid 1920s his work had taken on a more violent air, a greater physicality and an increase in temperature. His paintings of dancers and jazz musicians have a rhythmic pulse, hot colour and dizzy pattern and in highlighting these characteristics Picasso may have been reacting to music, rather than African tribal art, music that nonetheless had its roots in Africa and had come to Paris as a result of Prohibition in America. The figures in many of these paintings are obviously black, dancers and musicians that in many ways echo the startled characters of his revolutionary painting Les demoiselles d’Avignon. By now seventeen-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter had become his mistress and a series of more aggressive female bathers and nudes began to appear.

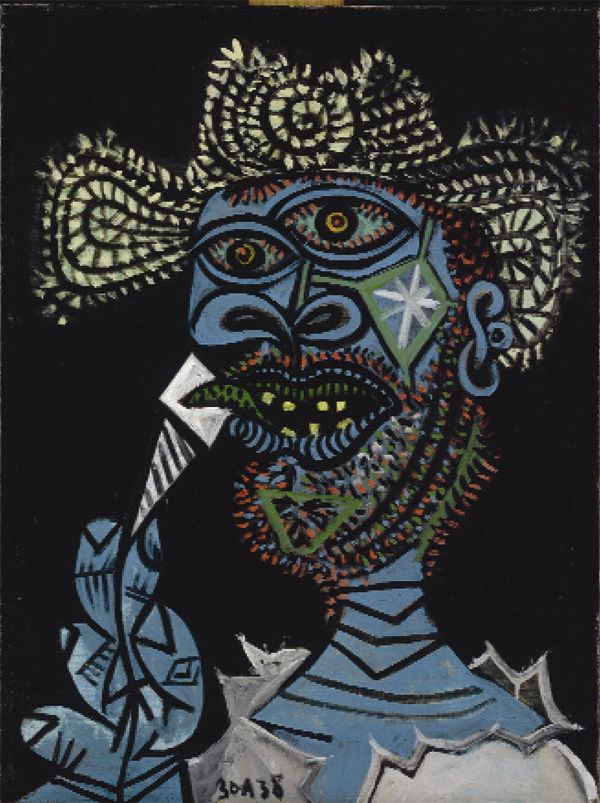

From the early 1930s, his ‘sur-realist’, as he referred to it, or fantastical period, heralded the introduction of softer, more compliant figures: we begin to encounter amorphous females, preening and reflecting dreamily in their mirrors, languorous and sensual, lost in a cosy reverie brought sharply back to reality by the rapid rise of fascism in Europe, the Spanish Civil War and the bombing of Gernika which elicited its own enormous and remarkable, monochromatic riposte. One painting that clearly shows the rupture is Man with a Straw Hat and an Ice Cream Cone (1938) a figure at once comic, wise and tragic, a clown, harlequin or pearly king with an uncomfortable truth brooding behind his crazy eyes.

Pablo Picasso

Man with a Straw Hat and an Ice Cream Cone, 1938

Musée Picasso, Paris(MP174)

© RMN / Jean-Gilles Berizzi / Succession Picasso / DACS 2009

We are now in the third room; Characters and Types. This title is in some ways unfortunate; Picasso’s extraordinary ability deftly to summarise personal characteristics in vivid graphic language, his distortions and reinventions became as the century developed the cartoonist’s gift. In their lampooning of modern art and in the quest for a convenient visual shorthand, satirists turned to the distortions of Picasso as a way of representing the sins and omissions of Modernism. Picasso’s own skills in the ridicule of friends and acquaintances from the present and the past are here and, for many observers, he now falls between serious invention and humorous mockery, the ludic and the ludicrous, a flaw that was to remain, some felt, for the rest of his life.

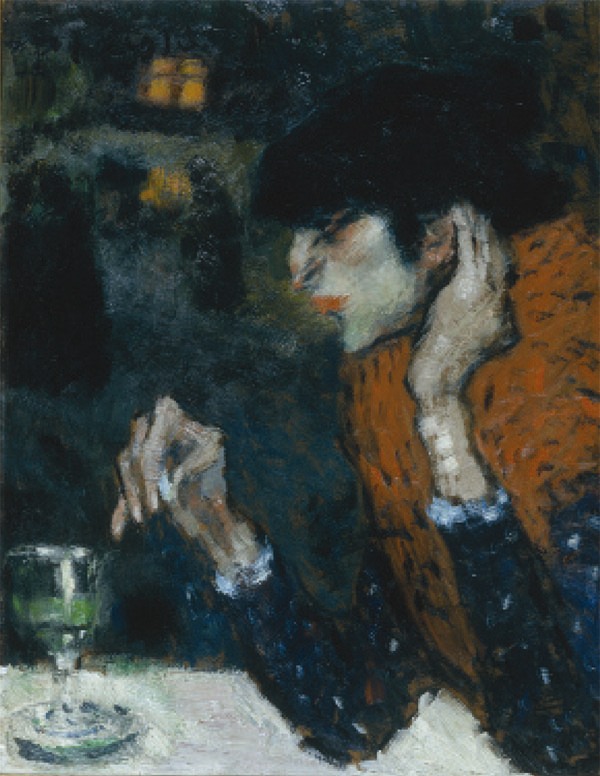

Some of Picasso’s more popular paintings occupy the fourth room, where, Models and Muses, The Pensive Sitter includes the famous Girl In a Chemise (1905) and The Absinthe Drinker (1901) as well as two paintings of Olga from 1922 and one of Fernande from 1905-6.

Pablo Picasso

The Absinthe Drinker, 1901

Private collection

© Photo courtesy of the owner / Succession Picasso / DACS 2008

If he had painted nothing else he would have been considered a great artist. These portraits from the first half of his life display a wistful sadness and a gentle sensitivity to the model that began to fade, as he grew older. The colours are subdued, the palette close, narrow, moving from warm to cold, the images are created with a tender touch, the paint stroked discretely on to the canvas. The artist seems to be as pensive in his painterly deliberations as are the sitters in their silent contemplation.

Room 5, The Still Life, shows the artist at his most sombre, with paintings drawn largely from his early years depicting skulls, fruit, wine jugs, a violin and bowls, many of them worked in the cubist style, described at the time as ‘a new way of looking at the world’. Initiated by Picasso and developed with Braque, one of his few acknowledged creative co-operations, Cubism evolved in three stages, beginning with the simplifications from Primitivism of around the mid 1900s (the dates are never precise), to the Analytical Cubism of 1907-14 and ending with Synthetic Cubism at the end of the decade. This was as close as he got to abstraction in his art, for the subject however deconstructed remained identifiable even in the most fractured and faceted surfaces of his nearly monochromatic cubist paintings. Paris remained his home for most of the Second World War, and he painted many darkly melancholic still-lives, a series of mementi-mori that continued intermittently until the mid Fifties and spasmodically until his death.

After the war the rivals were to come not from the past but from across the Atlantic. In the new world order Europe lost its cultural pre-eminence. Paris was no longer the capital of the art world, as American wealth and political and cultural expansionism began to reveal a new kind of art to the recovering world, while ironically for him, much of the innovation which permitted and heralded the changes that began to overshadow him had been developed in the slip-stream of his own daring experimentation.

A great deal of Picasso’s serious engagement with the past dates from this period. He was still the world’s greatest living artistic genius. His doves flew propagandist peace missions across the globe as the art world looked to new faces, new names and new ways of making art. His re-examination of the past intensified.

From the 1950s Picasso’s painting explored his familiar tropes of Figurative Modernism. In the final rooms of the exhibition entitled Variations, we confront his frantic stripping down and re-assembling of the art of the past. Paintings by Poussin, Velasquez, Delacroix and Manet are deconstructed and remade in rapidly evolving series, but always to the will of Picasso. The portrait after Velasquez of the Infanta Margarita Maria (1957) is one of a group of studies said to be important to the artist for its identification with his younger sister, Conchita, who had died of childhood diphtheria in 1895. The paintings exaggerate the formalities of Velasquez while utilising and emphasising Picasso’s own innovations. In our example the mirror tilts, the head and face are seen in Picasso’s by now customary practise of depicting two profiles simultaneously, the colour veering towards bright golden green on a dark ground. The Infanta is trapped, box-like, in the complex construction of her court dress, formally constrained by etiquette, her position fixed in a hierarchical royal order, perhaps Picasso’s lost sister, permanently alive, frozen in time.

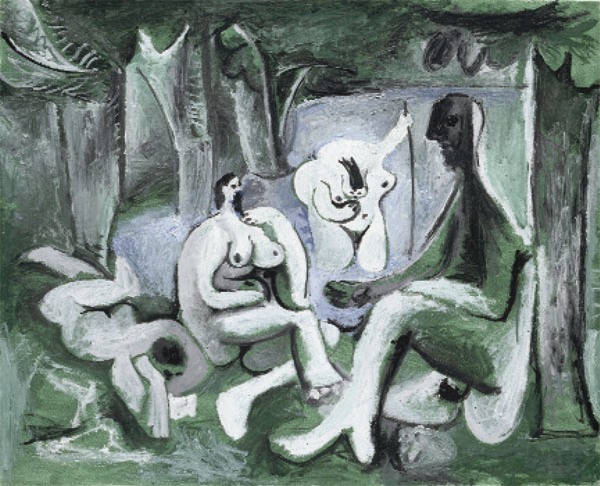

Manet’s once notorious Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, (1863) a painting that simultaneously outraged and excited polite Parisian society because of the moral and pictorial liberties it took with conventional social and aesthetic mores, is rendered down into a sea of salad-green by Picasso. The picnicking figures wilt and reform themselves as Picasso gently mocks bourgeois manners and conjures up the scandalous al fresco drama. He also made sculptural responses, some of which are shown here, they structurally rearticulate the flat, floppy painted forms. In his greenly cast paintings the cool fecundity of northern Europe lowers the heat of mixed feasting and bathing. Picasso removes the figures from nature and places them on stage, actors in a drama or on a film set which adheres playfully to his own pictorial ambitions.

Pablo Picasso

Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, after Manet, 1961

Musée Picasso, Paris (MP216)

© RMN / Jean-Gilles Berizzi / Succession Picasso / DACS 2009

Les femmes d’Alger (1955) after Delacroix, shows Picasso pilfering his own aesthetic past; he combines elements of late Cubism from his 1920s dancers and musicians and marries them to aspects of his Weeping Woman of 1937.

Picasso took great liberties with this painting, the figures are dramatically modified, bosoms and bellies exposed but sexually restrained by corset-like cubist contrivances. The allure of the seraglio is overshadowed by a fear of the feminine and as in much of Picasso’s later work the spectre of impotence, the possibility of blindness and the admission of failing power illuminate the scene balefully.

Pablo Picasso

Les femmes d'Alger, 1955

European Private Collection

© Photo courtesy of Libby Howie / Succession Picasso / DACS 2009

The riot of chaotic exuberance in Picasso’s 1962 response to Poussin’s L’enlévement des Sabines (1799) shows him in some sort of formal and emotional meltdown. The colour is bleached out, and the figures struggle to retain their anatomical integrity. Picasso’s anger at the bombing of Gernika, with its many civilian casualties, had remained with him, bolstered by the wartime occupation of Paris and magnified by subsequent revelations of Nazi atrocities and newsreel coverage of war in Korea and Vietnam. Poussin’s painting stood as a metaphor for rapacious killing and lust and here Picasso vents his disgust in this violent and dramatic re-interpretation.

Working from Goya’s Naked Maja (1797-1800) occupied him for much of the 1960s. Reclining Nude (1969) is one of a series of paintings and in this version an exhilarating celebration of the female form is somewhat muted by a ghostly echo of his terror at female sexual power.

Pablo Picasso

Reclining Nude, 1969

Private Collection

© photo Orlando Faria 2008 / Succession Picasso / DACS 2009

As the series evolves the figure grows, to fill the canvas, the hands, feet, bellies, breasts and eyes dominate as the psychological concerns of the artists raise the spectres of his anxieties.

This exhibition takes a small but representative sample of Picasso’s oeuvre, and makes an exhilarating and convincing case for his challenge to the past. During his long life he produced a colossal amount of work that was highly original and remains instantly recognisable. In every area in which he chose to work, with whatever medium, he excelled. At no time did he need to fear for his reputation, his place in the history of art is secure. As an artist of extraordinary power it is something of a surprise that he worried so much about his place in the Pantheon. He was a flawed man in many respects, and many suffered as a result of his cruel self-obsessions; his work however, remains, unforgettable, wrought from his own fears and passions, for he, too, knew pain and in exorcising his own demons he created a body of work unsurpassed by any master of the past and unlikely to be overtaken by any artist of the future.