Deconstruction, Reconstruction and Reclamation: The Art of Tim Davies

Anne Price-Owen on the Tim Davies exhibition, Between a Rock & a Hard Place which is being held at The Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea, 10 October to 6 December, 2009.

09.11.09

Tim Davies is one of our greatest contemporary artists. He continually surprises us with new and apparently disparate works, while simultaneously recalling themes related to his Welsh consciousness and cultural values. Far from being inward-looking, these are key features of identity, a universal concept important to us all whatever our cultural and social background.

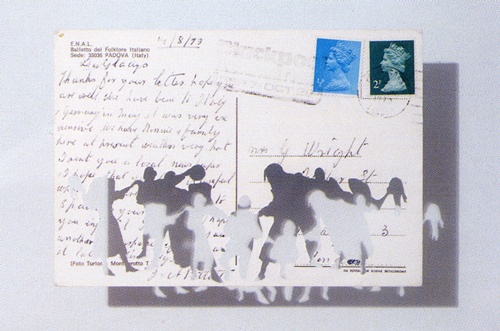

On entering the gallery’s spacious atrium we are confronted by sixty-four picture postcardshanging on the main wall. These continue the theme of Tim Davies’s Figures in a Landscape series. The figures themselves have been carefully cut out of the pictures, leaving only the landscapes - we see the ghostly white silhouettes of the indigenous people as if they’ve been blanked by the photographer.

Figures in a Landscape. (Photo © Tim Davies.)

Nevertheless, by framing the pictures between two sides of glass, and hanging them in front of the wall with strategically placed lighting, the shadows of the missing figures are thrown onto the wall, so that their appearance is doubled or sometimes trebled. This emphasis on the figures reinstates them as the focus of the compositions. Davies uses postcards to comment on both tourism and imperialism. By deconstructing the images, his aim is to dissipate the oppressor. Although his series of postcards of Bridges is thematically related, his tactic here is slightly different: the bridges remain, while their surrounding landscapes have been meticulously sanded away, leaving a totally blank background. These bridges have no context and are only identifiable by our recognising their designs, as in the Severn bridge, for example. This suggests a positive approach, that Davies is highlighting the function of these structures as instruments that connect two groups of people, in a kind of dialogue. But such connectors between people are fragile and need to be maintained. When the bridge is destroyed, as happened at Mostar during the war in Bosnia, the connection is defunct, and conflict, rather than understanding, can result.

In his series of studies in progress, Cathedrals, Davies’s treatment of the images of these structures makes them look as if they are exploding, or more accurately, imploding in on themselves, the original pictures having been cut up and reassembled as constructs of haphazard architectural detail. As in the Bridges series, the context of the buildings has been removed, but the retention of the blue sky reminds us that Davies uses blue as a symbolic mark of resistance to opperssion(see Planet, no.143:120-22), in Cathedrals, he alludes to the sublimation of one’s own culture by religious indoctrination.

Davies’s fascination with movement can be seen in his series of DVD installations, where as cameraman he runs around his subjects while they remain still. In his Cadet series of war memorials, while he records the Remembrance Day ritual of respectful immobility, his hand-held camera is busily circling those standing to attention, evoking the frenzy of the field of battle. His latest DVD, Kilkenny Shift, is a film of the servants’ backstairs in the luxurious Kilkenny Castle. Davies selected these stone steps in preference to the opulence of those the visitors ascended on their tour of the castle.

Kilkenny Shift detail. (Image © Tim Davies.)

At first, the film is deliberately slow as each succeeding step upwards is examined, and we can identify differences in each close-up of the horizontal stones which, in colour and texture, resemble a portfolio of charcoal drawings. The stately pace of the close-ups changes dramatically as Davies races downstairs, producing a vortex of confusing images. Alternating the film speeds evokes the plush, soft luxuriance of the unseen staircase as opposed to the durability of the hard, stone steps, and perhaps implies the servants’ climb on the one hand. On the other, their eagerness to be free of their drudgery, evinced in the footage of the giddying descent, is convincingly articulated by the skilful editing and splicing of the film.

In all of these exhibits, we are conscious of the connecting motifs that make this show such a successful and coherent body of work from Tim Davies where deconstruction, reconstruction and reclamation remain his triadic signature.