Y Lle Celf: Resources of Resilience for a Fragile World 04.09.17

Sara Rhoslyn Moore reviews Y Lle Celf art exhibition at the 2017 National Eisteddfod

and finds common thematic threads of international co-operation in the face of inequality and war; breathing new life into the Eisteddfod’s role as a festival of peace. She highlights the work of artists to watch out for in the future, and offers reflections on how the exhibition could evolve in forthcoming years to best give prominence to 21st-century Welsh visual art.

Y Gorchudd Llwch by Christine Mills. Photograph © Aled Llewellyn

The combination of visual and applied art at the 2017 Lle Celf exhibition gave a sense of unity: not only expressed through the common language of Welsh, but also stimulating a universal consciousness of internationalism, with themes of peace and trans-cultural co-operation, and resilience in the face of loss, inequality and war.

Welcoming the visitors as they entered was Y Pram yn y Cyntedd/ The Pram in the Hall, an enormous iron pram created by metalworker, Angharad Pearce Jones. This challenges Cyril Connolly’s famous quote on how parenthood is an ‘enemy of good art’, drawing on Jones’s experience of being an artist and mother. The triangular foundation of the three-wheeled pram mimicked hierarchical structures, such as patriarchy, and the persistent power of inequality.

I could not help but also relate the empty pram to the empty chair, the Black Chair awarded to Hedd Wyn after he had been killed at Passchendaele. Christine Mills responds to the centenary of Hedd Wyn’s death with her sculpture made of wool and well-water from Yr Ysgwrn, Trawsfynydd, the poet’s home. Mills’ ghostly white shell of the black chair on its plinth, comparable to a throne, reminds us of the need to hold the powerful to account for lives lost in pursuit of their power games.

Three portraits painted by Annie Suganami entitled Paradwys Goll/Lost Paradise also evoke loss – alongside endurance. They express the artist’s deep concern for the state of the world socially and environmentally. They are painted with emotional acuity and technical skill. The use of the colour blue intensifies the sincerity of their depiction as nameless icons who have shown strength in the face of adversity: they are symbols of survival in uncertain times.

Similarly, Peter Davies’ Survival combines fragile and strong materials to draw attention to the struggles different individuals face. Fired on to glass-fused panel is a black-and-white image of a topless man who is partially hemmed in by a steel obstacle. The nature of the restrictions he experiences is left open, which enables a personal interaction between the piece and the viewer, as each individual experiences their own restrictions in a world of differences, and the challenges involved in negotiating society’s perceptions of us.

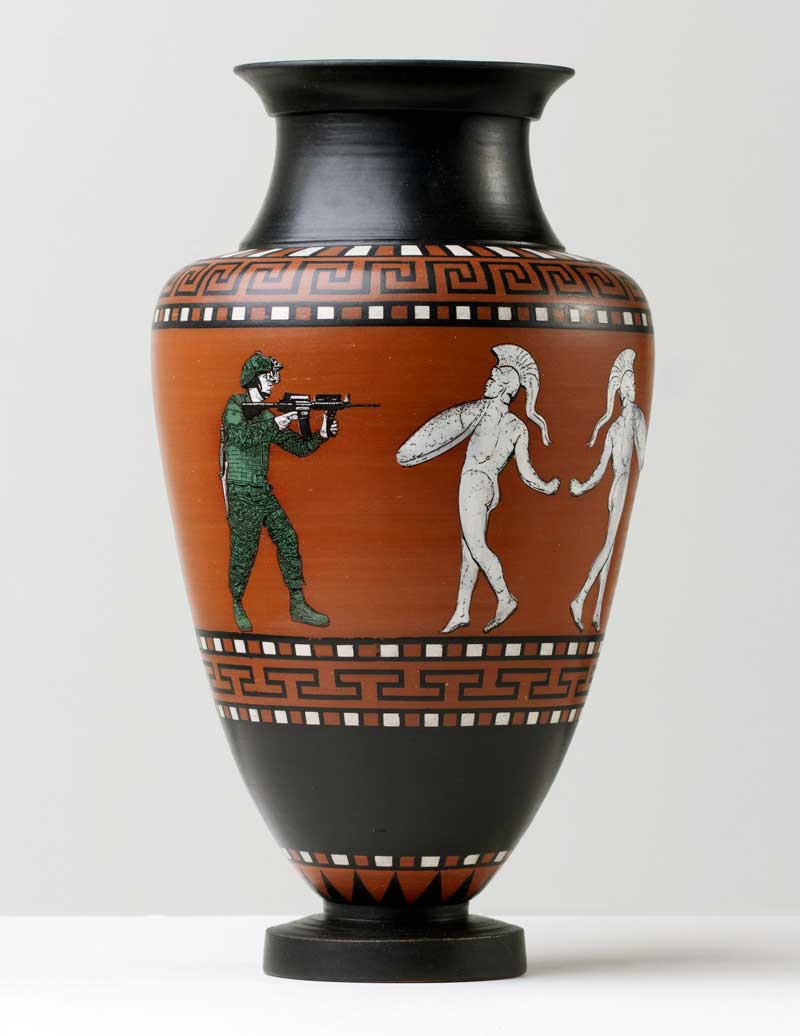

How to win friends and shoot people by Ray Church © Ray Church

A number of the works relate to Wales’s interconnectedness in the world, particularly its relationship with the rest of Europe, which is especially apt after the EU referendum. Drawing inspiration from other cultures, Ray Church creates a dialogue between the classical and the contemporary with his Ancient Greek-inspired vases, which reference 21st-century socio-political issues in the manner of Greek depictions of myth and cultural values. Jack Burton’s collage of photographs explore his relationship with Europe, specifically his travels in Athens and Berlin. Julia Griffiths Jones’ Room Within a Room, winner of the Gold Medal for Craft and Design, brought to life sketches she had made in Bratislava and Abergwili by ‘drawing’ with wire to create a multi-layered tableau of Slovakian and Welsh domestic interiors. The costumes, artefacts and comforts of the hearth found in Wales and Slovakia were remarkably similar, as is the traditional significance of the colour red. The urge to walk in among the 3D effect room, which resembled a virtual reality scene, was so tempting!

Stills from Dim Teimlad Teimlo Popeth © Gethin Wyn Jones

Returning to themes of war and peace, as similarly explored by Christine Mills, Gethin Wyn Jones offers a brave and honest piece Dim Teimlad Teimlo Popeth. Filmed as a ‘luxurious goods’ commercial, these seductive close ups are of an AK-47 assault rifle, the most destructive of all guns sold globally, and responsible for an estimated quarter of a million deaths per year. AK-47s appear on national flags, video games and films, encouraging a continuation of their disturbing appeal among every generation. It is hard to walk away unaffected by these disturbing truths, all the more poignant at this festival of peace.

Morgan Griffiths’ Dada-esque two-part large collage depicting different eras explores the fragmented interaction between history and the future. This way of thinking captures the essence of Gethin Wyn Jones’ piece: the confusion that comes with failing to look for or understand fragments as a whole, as global phenomena, like the arms trade, which affect us all.

Installation © Cecile Johnson Soliz

Cecile Johnson Soliz was the winner of the Gold Medal for Fine Art. Her giant paper installations involved twisting, folding and wrapping ̶ her creative process must have required great physical effort using the whole body, as well as the thinking process to work on such a large scale. They reminded me of the importance of play in creativity. However, the back-story of the physical movement and freedom involved in the making of the work proved more evocative than the finished pieces.

There were many events, happenings and collaborations at Y Lle Celf involving, poets, singers, even archaeologists, which were fantastic. Now this needs to happen in reverse. Why were no visual artists commissioned to document the opening and chairing ceremony, given its importance in marking the anniversary of the notorious Eisteddfod of the Black Chair? This could also have been an opportunity to pay homage to Welsh war artists. There is still a long way to go in recognising and valuing visual art as highly as other fields within Welsh culture.

Looking to the future, we have now entered the digital age, and more attention needs to be given to audience interaction with film art. The seating offered for film art in Y Lle Celf was horizontal plinths ̶ uncomfortable, dated and bordering on unacceptable, especially for a 30 minute film. The art is therefore unlikely to get the attention it deserves.

Curators and the architects who collaborate with Y Lle Celf could create a very interesting exhibition space if they built the structure with the context of the work in mind. Plinths are old-fashioned, but architects could incorporate them into the design of the space, even build in elements from some of the architectural work which is showcased in the exhibition, which would bring them to life in new ways.

You can experience an online 3D model of Y Lle Celf 2017 here

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

Sara Rhoslyn Moore is a visual artist and writer from Bethesda. She graduated in 2015 from Trinity Saint Davids at Carmarthen with an MA in Fine Art and is winner of the David Tinker Award 2014 from the Contemporary Art Society of Wales. Sara's interests lie in Welsh culture and identity, particularly the future of Welsh language.

If you liked this you may also like:

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…