We will not see his like again 30.07.18

M.Wynn Thomas remembers Meic Stephens

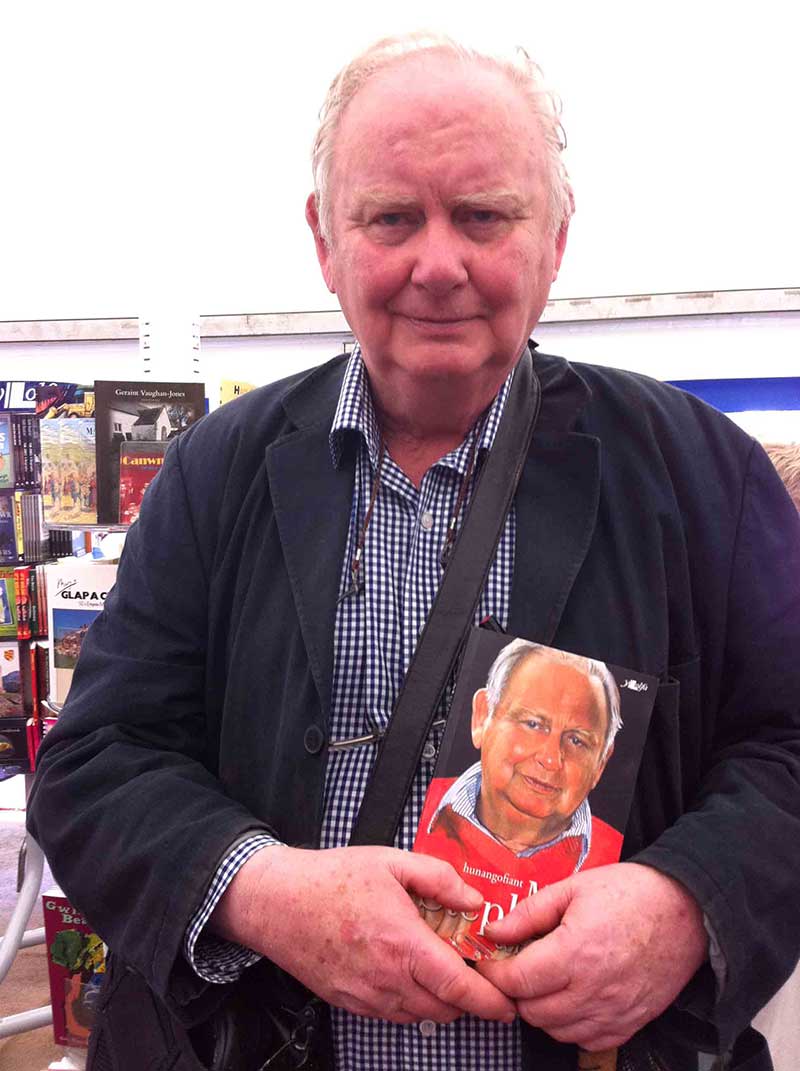

Photograph of Meic Stephens taken during the 2012 Eisteddfod. Meic is holding a copy of his Cofnodion, published by Y Lolfa. Image © Y Lolfa

If you would seek his monument, look around you.

Rewind fifty years and the literary landscape of Wales would have looked very, very different. Grants to authors, grants to publishers, block grants to publishers, literary periodicals, literary awards, international travel, creative writing centres – there were none of these available, either for Welsh-language or for English-language writers. They are all largely the work of a single figure – Meic Stephens – during the quarter of a century he served in post from 1967 onwards as the founding Director of Literature for the Arts Council of Wales. Previously he had briefly been a school-teacher in Ebbw Vale and then a journalist with the Western Mail.

Not that his work of cultural transformation started with the Arts Council. Before that, he had had a hand in writing ‘Cofia Dryweryn’ on a boulder near Llanrhystud, had blocked the bridge at Trefechan, Aberystwyth, had aided and abetted those who ran a free Wales radio station from a Merthyr attic, had lived in a kind of commune presided over by Harri Webb, and had been one of the band of young men who hoisted Gwynfor Evans onto their shoulders in Carmarthen in the heady aftermath of the 1966 election of the first Plaid Cymru MP to Westminster.

Meic had the physical presence, as well as the resourceful intelligence, nimbleness of wit, and imposing eloquence, to dominate any company. I witnessed this when I paid a brief visit to the Soviet Union with him and another committee member in 1989. It was December, bitterly cold, and while Moscow was blanketed in thick snow there was glasnost in the air. Wherever we went, apparatchiks instinctively gravitated towards Meic, well over six feet tall and bulky.

A day or two after our arrival at the grim Pekin hotel we felt peckish around 6.30pm and so resolved to explore the restaurant, although glumly aware that however lavish the printed menu all that would actually be available would be borsch. Halted at the door we approvingly noted the large room was completely empty. But we were firmly denied entry. ‘The restaurant is full’, announced the guardian waiter firmly. We stared in disbelief, first at him and then at the empty room; we then protested politely, but increasingly volubly. But the waiter was not to be budged and still resolutely barred our way. Eventually, Meic, an old Russia hand, could stand it no longer. As I did my very best to vanish into the woodwork, he drew himself up to his full imposing height, pressed his bulk against the unfortunate waiter until he was virtually pinned to the door. ‘Look here, butty,’ he said, ‘you heard of London Guardian newspaper? Me, journalist from The Guardian. Unless you let us in this story will be front-page news tomorrow.’ The waiter visibly paled and wilted. He scurried away and returned with an ingratiating manager. With no more ado we were ushered through the restaurant to a back room. There not only were we provided with a slap-up meal but also entertained by Gypsy musicians spirited up to placate us. And then, eventually replete, we made our solemn exit through a restaurant that was still ‘full’.

It was this rebellious, combative side of Meic that both enabled him to achieve wonders as Director of Literature and also ensured that at times he seemed to have almost as many enemies as he had friends. He never shirked controversy. And not the least important of his remarkable achievements was the steady fostering of a rapprochement between Wales’ Welsh-language and English-language writers, a development which in some ways paved the way to the public acceptance – and even celebration – of a bilingual and bicultural Wales.

His editing of The Companion to the Literature of Wales remains a towering landmark of a cultural achievement of course. So, too, does the remarkably comprehensive poetry anthology he edited for the Library of Wales Series. But also important were the opportunities he afforded writers and other Welsh artists from the seventies onwards to reflect on their careers. Then there was the groundbreaking Writers of Wales series he co-edited with Brinley Jones, and that in due course attracted admiring comment even from that major English poet, the notoriously curmudgeonly Geoffrey Hill. His anthologies were legendary, and his Welsh-English translations numerous. A fine anglophone poet when young, Meic it was who launched Poetry Wales, a daring initiative that eventually provided a home for previously exiled talents such as John Tripp, Leslie Norris and Dannie Abse, and that offered a launchpad for brilliant new careers such as that of Gillian Clarke. The creation of this periodical set in train a chain reaction that produced the first dedicated Welsh anglophone press in Poetry Wales Press, subsequently Seren Books.

Ever proud of his journalistic skills, he eventually became the obituary writer at the Independent solely responsible for memorialising notable Welsh women and men. And it was the opportunity to pass on his skills as a professional writer (a profession he greatly admired and the development of which in Wales he always attempted to facilitate) that he perhaps most valued in his post-Arts Council work at the University of Glamorgan. He wrote fascinatingly about his own life and family background, as well as about the semester he spent in Utah in the company of his friend Leslie Norris, and he produced a biography of Rhys Davies in short order that scooped a Welsh Book of the Year Award in 2014. His important work through the Rhys Davies Trust (of which he was Secretary), including the placing of commemorative plaques for Welsh writers in their native districts, was one outcome of his devotion to safeguarding the legacy of notable Welsh anglophone writers, many of whom – such as Glyn Jones, Harri Webb and Leslie Norris – had been his close friends.

My last public meeting with him was when I chaired a discussion of the important, and monumental, final anthology he co-edited, The Old Red Tongue. This he rightly regarded as a crowning achievement. ‘John Davies sends his regards,’ was his conversational opening. I had no idea who John Davies was, and so returned a politely noncommittal reply.‘You don’t remember, do you?’ he sardonically queried. ‘John Davies was the character I invented in the pryddest you failed to praise in your Eisteddfod adjudication.’ Once again, he’d got the better of me. And nothing could please him better. He remained utterly irrepressible and unignorable to the last.

So look around you. We will not see his like again.

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

M. Wynn Thomas, Professor of English and Emyr Humphreys Professor of English, Swansea University, is a Fellow of the British Academy and of the Learned Society of Wales. All That is Wales, the latest of his two dozen books, won a Welsh Book of the Year award for 2018.

If you liked this you may also like:

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…