Should the Welsh Assembly adopt a definition of Islamophobia?

by Mairi Hughes

Following the UK government’s rejection of the APPG on British Muslims’ definition of Islamophobia, could Wales adopt it? Mairi Hughes reports on a wide range of perspectives within the public sphere on the complexities of fighting prejudice via a formal definition.

Mosque in Crwys Road, Cardiff © Ceridwen (CC BY-SA 2.0) https://bit.ly/2YSxjsZ

On 15 May 2019, the UK government rejected a definition of Islamophobia proposed by the All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims. Exactly seven days later, Plaid Cymru’s Leanne Wood stood up in the Welsh Assembly and urged the Welsh Government to make a statement on the impact this rejection had on community cohesion.

While Westminster rejected the APPG’s Islamophobia definition, it has gained support across the UK from the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats, all parties represented in the Scottish Parliament and Plaid Cymru.

Is this definition the way forward in stamping out anti-Muslim sentiment, and what would the adoption of this definition mean for Wales?

A pressing problemThe APPG’s report outlining their Islamophobia definition contains various attention-grabbing green boxes scattered throughout its 72 pages. Within each green box is an anecdote from an anonymous British Muslim detailing a first-hand encounter of anti-Muslim hate crime: lit fireworks posted through letter boxes, children being sworn at and spat on, young girls beaten on account of their headscarves.

It is clear that Islamophobia is a palpable problem which is sadly engrained into the fabric of our society. This is demonstrated by the latest figures, which stated that anti-religious hate crime increased by 40% between 2016/17 and 2017/18 in England and Wales, the biggest increase in any recorded category of hate crime. Over half (52%) of all victims of these hate crimes were British Muslims.

The picture in WalesThe issue of anti-Muslim sentiment has been a growing concern in Wales as of late. Abdul Azim-Ahmed, deputy general of the Muslim Council of Wales, feels there are two dimensions to this problem in the country. As well as the problem of hate crime demonstrated by the figures above, he also raised concern about Islamophobic sentiment within the Welsh Assembly.

He said: ‘Harassment in the street or in workplaces, that’s the dimension that’s right across the country…We also have a high number of assembly members from UKIP and as a party, in terms of the policies they put forward and the actions and behaviour of their elected members, it’s been a very Islamophobic party. And that’s embedded within the National Assembly.’

In 2003, members of Wales’ Muslim community came together to form the Muslim Council of Wales. An affiliate of the Muslim Council of Britain, this was founded to represent the unique needs of the Welsh Muslim population.

Abdul Azim-Ahmed feels Wales is currently behind the rest of the UK in creating equality for the Muslim community.

He put forward that the community is ‘a very small minority in Wales, it’s lower than the national average, which means that there is a different dimension as well, we’re more likely to be spread far geographically …

We have less institutional development … Our own organisations, institutions and mosques are smaller and less developed and less financially established comparative to some organisations in England.’

Wales’ Muslim community is certainly feeling the sting of anti-Muslim sentiment in the country. Many have placed the blame for this on a significant far-right presence in Wales. The co-ordinator of the Welsh anti-radicalisation project Resilience, Tony Hendrickson, recently labelled Wales as a ‘hunting ground’ for far-right groups, and went on to make the case that far-right extremism is far more prevalent than Islamist extremism in Wales.1

This has not gone unnoticed by policy-makers. Plaid Cymru’s Leanne Wood comes to the same conclusion as Abdul Azim-Ahmed, feeling that far-right sentiment has seeped its way into the Welsh Assembly due to parties such as UKIP gaining traction in the country.

She said: ‘I’m not convinced that in Wales we’ve got our head around this problem collectively yet as much as we should … It’s not a new phenomenon, although I do get the sense that people seem to be more emboldened now, and I think that’s in relation and connection with some of the rhetoric from the more far right politicians.’

Defining IslamophobiaWestminster’s APPG on British Muslims was formed in 2017 and dedicates itself to establishing what challenges and discrimination British Muslims face on the ground. APPG member and former Chair of the Conservative Party Baroness Warsi has stated that in the UK, Islamophobia passes the ‘dinner table test’2. An out of place dessert spoon would cause more outrage than a candid anti-Muslim remark at the dinner table.

It is on these grounds that the APPG says defining Islamophobia would be the next logical step in tackling anti-Muslim discrimination in the UK. The definition which the APPG have unveiled, formulated following consultation with Muslim communities, academics and lawyers states: ‘Islamophobia is rooted in racism and is a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness’.

The APPG state the definition aims to protect Muslims from all forms of discrimination while simultaneously safeguarding society’s ‘fundamental right’ of criticism of religion.

However, for some in the public sphere this distinction is not sharp enough. Tim Dieppe of the conservative Evangelical lobby group Christian Concern said of an Islamophobia definition: ‘Anti-Muslim behaviour, or threats, or violence, or whatever it might be, should be caught, but criticism of Islam should not be.’

Rejection of the definitionThe UK government praised the work of the APPG on British Muslims, however it said that the wording of their definition needed further consideration. Both the definition’s labelling of Islamophobia as ‘a form of racism’ and its negative connotations for free speech were criticised.

Many have viewed this rejection as yet another indicator that anti-Muslim sentiment lives and breathes among the Tory party.

Nonetheless, criticism of the definition was not confined to the Conservative government. Following the unveiling of the APPG’s definition, several academics, national organisations, journalists and others came together to sign an open letter to Sajid Javid, officially opposing the definition.

No less than 44 signatures marked the bottom of this letter, which is headed with the title ‘Islamophobia Definition Threatens Civil liberties’.

The National Secular Society was one notable organisation who signed the open letter to Sajid Javid.

A spokesperson from the National Secular Society, Chris Sloggett, made it clear that ‘Anti-Muslim hatred is a growing problem which must be taken seriously.’

However, Sloggett added, ‘We’re concerned that the APPG on British Muslims’ definition of Islamophobia is too vague, particularly because it protects ill-defined “expressions of Muslimness”. Its adoption risks shutting down legitimate criticism of Islamic practices.’

Tim Dieppe of Christian Concern echoed these issues regarding limitations on criticising religion. He said: ‘We don’t want ever increasing definitions, ever increasing definitions will just prohibit free speech and get people more and more scared about what they can say and what they can’t say … Similarly, people should be allowed to criticise Christianity, I don’t want a legal definition of Christianaphobia.’

Tackling hate crimeThe debate around the APPG’s definition of Islamophobia has struck up a wider conversation across the country around how hate crime should be tackled in the UK.

As Plaid Cymru continues to encourage the Welsh Assembly to adopt the definition, Leanne Wood argued: ‘This is always the dilemma with dealing with any kind of racism, sexism. Free speech comes with limitations and responsibility, and I’m of the view that if your speech harms other people, then you don’t deserve the freedom to spout that.’

Those against the prospect of Wales adopting the definition point to current legislation in place in the country. Under the Equality Act 2010, religion is a legally protected characteristic. Tim Dieppe argued: ‘It’s already used in law, and people have been prosecuted for anti-Muslim crimes, and convicted for anti-Muslim crimes, and that’s very clear, and that suffices.

However, those in support of the definition feel that a failure to adopt this will allow the critical problem of anti-Muslim sentiment to slip to the bottom of the political agenda.

Leanne Wood put forward: ‘If organisations like Westminster, and even the Assembly, are not prepared to sign up to that particular definition, then what is it that they are prepared to sign up to, that goes far enough?’

Moving ForwardWhen Leanne Wood stood up in the Welsh Assembly and asked for comment on the impact Westminster’s rejection of the APPG’s Islamophobia definition would have on community cohesion, the Assembly responded that they were in talks with the Scottish government, ‘with a view to adopting the definition’.

Hardeep Singh of the Network of Sikh Organisations, whose signature appears on the open letter to Sajid Javid, said: ‘Generally with these sorts of subjects, it seems to be quite binary. But, if you look at the granularity of the detail, you realise it’s actually far more complicated than a group wanting to have a definition, there’s so many other things involved in this.’

The debate around how policy-makers should be ensuring the defeat of anti-Muslim sentiment, and the appropriateness of formal definitions in challenging hatred and prejudice remains on the political agenda, and has unravelled in all its complexity. As the Welsh Assembly considers its next move, it seems this decision will set a significant precedent for how hate crime should be tackled.

-

Notes:

- 1: BBC, 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-46557076

- 2: Reported by the BBC, 2011 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-12240315

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

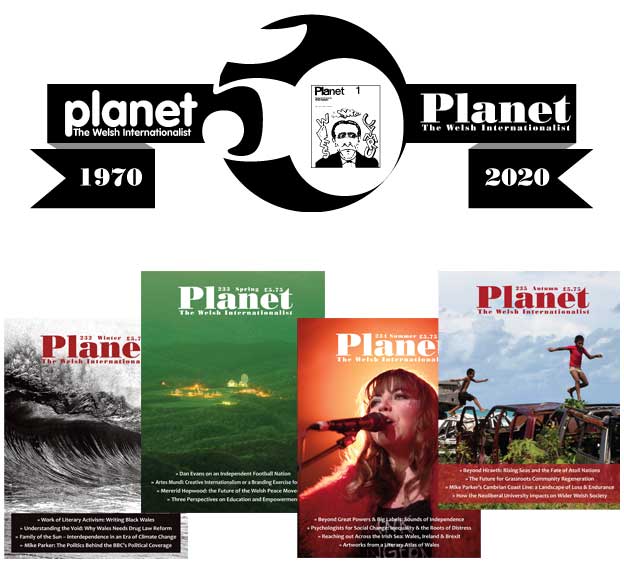

“Since its inception almost half a century ago, Planet has consistently pushed our boundaries of discourse. It has challenged, provoked and inspired, and always remained true to its own subhead (‘The Welsh Internationalist’) by placing our small country in far wider contexts. In a world where so many are hell-bent on building barriers and narrowing horizons, we need it now more than ever.” - Mike Parker, author.

You can contribute to Planet's future following successive cuts to our funding by taking out a Supporters' Subscription. Our new Supporters’ Subscription packages include a range of exclusive products, benefits and reading experiences drawing on nearly 50 years of Planet's history. For more information please click here.

About the author

Mairi Hughes currently works as a magazine journalist for DC Thomson in Dundee (Scotland) and is also a columnist for The Irish Voice newspaper, based in Glasgow. She lived in Cardiff in 2018 while completing her Masters in Magazine Journalism at Cardiff University.

If you liked this you may also like:

Planet Video: Digwyddiad Planet ar gyfer yr Eisteddfod, 2019

Mae’n bleser mawr gan Planet gyflwyno ein digwyddiad ar gyfer yr Eisteddfod 2019. ‘Beth yw ystyr “rhyng-genedlaetholdeb Cymreig” yn 2019?’ oedd teitl y digwyddiad.

When Vice Came to Swansea

Congratulations to the winner of our 2019 Young Writers’ Essay Competition. Mark S. Redfern argues that a globally popular Vice documentary, repackaged for YouTube, gives a condescending and sensationalist angle on Swansea’s heroin crisis, and has left a poisonous legacy in capturing for posterity humiliating depictions of the protagonists, and misrepresenting working-class Welsh culture.

Planet at 50: A Celebratory Event Hosted by the National Library of Wales

In 2020, Planet celebrated 50 years as Wales' liveliest cultural and political periodical. Watch this video of founding editor Ned Thomas and current editor Emily Trahair in conversation with author Mike Parker at this event from December 2020 to see what's changed, what hasn't, and why a publication subtitled 'The Welsh Internationalist' is needed now more than ever