Thinking beyond ‘hippies’ and ‘hambones’: How radical environmental reform could save us all 03.06.19

Kirsti Bohata reflects on her experience of protesting with Extinction Rebellion and points to how existing alliances between environmentalists, farmers and the national movement can be strengthened for the benefit of everyone in Wales.

Kirsti Bohata at Extinction Rebellion protest in London, 2019 © Deri Morgan

When Extinction Rebellion (XR) launched last year, it quickly gained traction in Wales. XR has three simple demands: for the government to tell the truth about ecological emergency caused by climate breakdown and loss of biodiversity; for net zero carbon by 2025; and to establish citizens’ assemblies to oversee the process. These demands are presented by self-organising groups willing to engage in peaceful civil disobedience. From the start, people from Wales have been well represented in high-profile actions, from gluing themselves to the doors of government ministries in November to the naked protests in the Houses of Parliament. Groups from Wales and Bristol held Oxford Circus in the April rebellion, taking turns to lock or glue themselves to the now-iconic pink boat, which was towed into place by an organic market gardener from west Wales. The kitchen set up in the middle of the road at the protest campsite at Marble Arch which provided thousands of free meals to activists and many homeless people was run by a woman from north Pembrokeshire. I spent my first shift at the pink boat practicing my Welsh with a grandmother and Welsh teacher who had superglued her hand to the boat and was arrested there the next day. Machynlleth Town Council was one of the first in Wales to declare a climate emergency in January of this year. Carmarthenshire County Council followed in February, and the Welsh Assembly declared a climate and ecological emergency on 1 May. As I write, it looks as if the M4 relief road will be scrapped.

Extinction Rebellion protest, London 2019 © Kirsti Bohata

Wales was ready to act when this movement kicked off in part because there are strong pre-existing links with environmentalists. One of the founders, Roger Hallam, has an organic farm near Llandeilo, and since the late sixties incomers seeking low-impact and self-sufficient lifestyles have formed communities which are now in at least their third generation. But this movement is not solely the preserve of what – when I was a child at Ysgol y Preseli in Crymych – were called ‘the hippies’ (in contradistinction to ‘the hambones’ – farmers). Yes, there are plenty of ‘hippies’ involved, but the distinction between hippies and hambones and the cultural tensions that playground name-calling identified doesn’t represent the far more integrated and complex picture in Wales today.

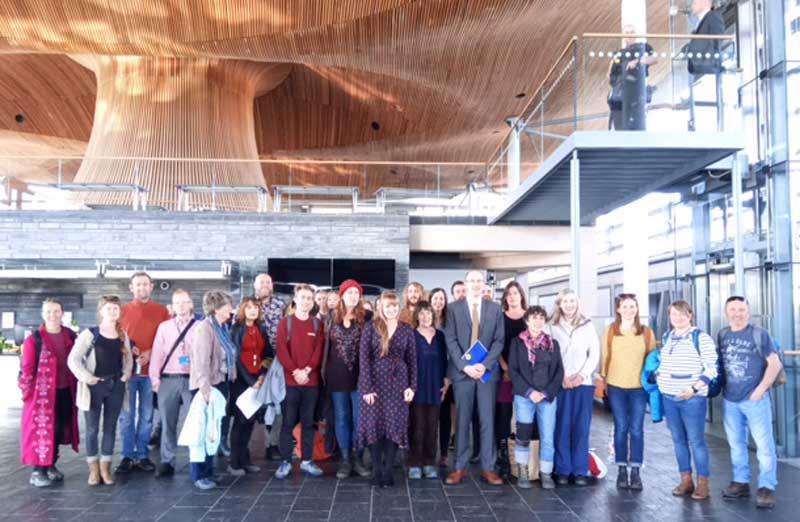

Declaration of Climate Emergency at the Senedd 1 May 2019 ©Anna Munro

It was Plaid Cymru councillors and AMs working in collaboration with local XR activists who led the call to declare a climate emergency in Carmarthen and the Senedd. Leanne Wood spoke alongside Welsh Labour AM Jenny Rathbone at the Wales-wide Extinction Rebellion protest in Cardiff on the 9th of March. Plaid’s green agenda dates back at least as far as the 1992 Plaid-Green electoral pact forged by Cynog Dafis, which saw him elected to represent Ceredigion. This alliance drew new voters who could embrace an outward-looking small-nation nationalism aligned with an internationalist green agenda. Despite the failure to renew this alliance, many of the new voters remained loyal to Plaid, and Plaid’s green credentials (though muddied by an incoherent position on nuclear power) allowed it to pick up votes in the recent European elections.

The real challenges for XR and Wales lie ahead. XR’s three demands focus on putting pressure on politicians to act, but deliberately do not propose policy solutions. So what should be the focus in Wales, which has limited legislative power? There is goodwill at the Senedd, but also very challenging conditions. We have renewable energy sources galore and are a net exporter of energy, but we do not benefit directly as a nation. We have a woefully inadequate public transport infrastructure, no electric railways, and underinvestment in charging points for electric vehicles. Meanwhile, Wales is experiencing a biodiversity catastrophe largely fuelled by farming practices, and to transform this situation will require a drastic overhaul of funding and regulation.

Biodiversity and FarmingIn April 2019, XR amended its demands to acknowledge the biodiversity crisis, which just as much as climate change, threatens the survival of our civilisation and most of the species on the planet. Agricultural practices are at the heart of addressing biodiversity and also account for about 12% of global carbon and 47% of methane emissions which are contributing to climate breakdown.

Farming is an emotive and culturally charged topic in Wales. Coming home between stints at the April rebellion in London I went to the funeral of our immediate neighbour, a farmer in his fifties. In the eulogy spoken first in Welsh and then in English, his daily battles and endurance as a livestock farmer were linked to the bravery and stoicism with which he faced terminal cancer. I was reminded of R. S. Thomas’s heroic farmer: ‘He too is a winner of wars/enduring like a tree under the curious stars’. How do we negotiate the symbolic power of this embattled figure of tradition and culture and language at the same time as moving to an ecologically sustainable system of agriculture?

The facts are stark: soil depletion, catastrophic pollution of waterways from the toxic waste produced by intensive dairy farming, ‘insectageddon’. Recent reports show a massive decline in wild plants, insects and the birds which depend on them and, of the 218 countries assessed globally, Wales is in the worst 25% for biodiversity loss. Yet the call for ‘rewilding’, often made from outside Wales, can sound like another version of appropriation. Wales as a tabula rasa, a playground, water source, energy supply or, now, ecologically restored wilderness – serving an Anglocentric agenda at the expense of Welsh culture.

It’s nothing new. In 1975 Raymond Williams recalled

a young bureaucrat … describing rural mid-Wales as a ‘wilderness area’, for the outdoor relief of English cities. He never understood why I was so unsocially angry. … [H]ere was he… looking on a map at rural Wales: at fields and hills soaked with labour, at the living places of farming families, and not even seeing them, seeing only a site for his wilderness. He had a friend, an economist, who used to prove to me, once a week, that the sheep, by nature, is an uneconomic animal, and that all this marginal farming, with returns on capital that would cause instant suicide in the Barbican, must simply be written off. ‘And the people with the sheep?’ I ventured to ask. ‘Of course, in that capacity,’ he replied without hesitation.1

There is no doubt that modern farming practices have been catastrophic. Yet the attack on farming practice must not become an attack on farmers. How do we find a balance between supporting farming and acknowledging generations of labour, whilst changing farming practice? It was a surprise to me to discover that agriculture – which occupies 80% of Welsh land – makes up just 0.59% GVA in Wales,2 rising to a little over 1% with subsidies included. It employs 3.62% of the population (proportionately higher than England and Scotland, but lower than Northern Ireland). Perhaps this data might offer some hope that we can as a nation afford to make changes, via subsidy and careful planning, that would greatly improve biodiversity.

As we move out of Europe, and as the EU Common Agricultural Policy itself looks set to be reformed, we must place biodiversity and climate change at the top of the priorities for farming subsidy. Moreover, farming is an industry that needs the infrastructure and facilities (biodigesters anyone?) to produce food and manage the countryside in responsible and sustainable ways. It is in everyone’s interests – farmers and environmentalists alike – to make these changes. Nor should this be seen as a direct challenge to Welsh traditions – a return to some of the mixed methods of the past, such as the mass reintroduction of caeau ysbyty, the hay meadow ‘hospital fields’ which used to be a feature on livestock farms is one urgent and achievable step. ‘Rewilding’ doesn’t have to mean desertion of the land: ‘agroforestry’ – which sounds grim but means the planting of trees on farms also used for livestock and crops – is one strategy, as is the support of high quality, high welfare and organic methods of food production.

This isn’t about lifestyle choices or even culture wars, it’s about the immediate survival of our children. In the coming decades climate and biodiversity breakdown and the attendant social stresses will force radical changes in land management and use. The Welsh landscape and the lives lived on it will be transformed. The challenge for XR, for Plaid, for Wales and the rest of the world, is to make the right changes now, to protect and empower people at the same time as we undertake radical reform of our economies. The ‘hippies’ and ‘hambones’ need to work together.

Extinction Rebellion protest, London 2019 © Kirsti Bohata

This article was amended on 12.06.19 to include a reference to Jenny Rathbone AM speaking at the XR protest in Cardiff on the 9th of March.

-

Notes:

- 1: Raymond Williams, ‘Welsh Culture’, in Who Speaks for Wales ed. Daniel G. Williams. (University of Wales Press, 2003). pp. 6-7

- 2: GVA measures the contribution to the economy of an industry or sector. Agriculture’s share of GVA in the UK as a whole was 0.48% in 2016. In Wales, agriculture’s share of GVA is above the UK average at 0.59%, which is behind both Scotland (0.88%) and Northern Ireland (1.08%) but greater than that in England (0.42%). Senedd Research, ‘The Farming Sector in Wales Research Briefing’ (October 2018), p.3. http://www.assembly.wales/research%20documents/18-057%20-%20farming%20in%20wales/farming%20in%20wales-web-english.pdf

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

Kirsti Bohata is a Professor in the Department of English and Creative Writing at Swansea University, and Director of CREW, the Centre for Research into the English Literature and Language of Wales at Swansea University.

If you liked this you may also like:

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…