An existential crisis? Reflections on a future direction for the Tories after a shock election result 03.08.17

In the third in a series of Planet Extra articles giving in-depth reflections on the 2017 General Election from different perspectives, Iain Lewis offers a detailed insight into why the Conservative Party lost their majority in the election, and suggests how the party might recover their standing in Wales and beyond…

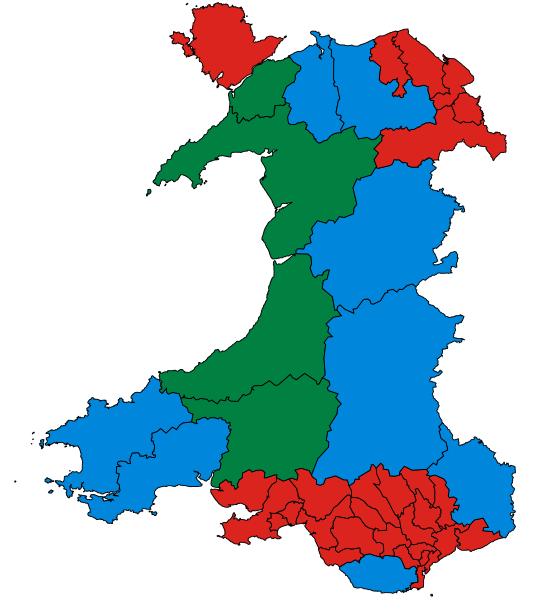

Wales Parliamentary Constituency 2017 Results © Brythones.

The most unexpected general election result since 1974 has triggered the Conservative party’s most serious bout of internal soul-searching and recrimination in decades. Party historian Sir Anthony Seldon – biographer and confidante of John Major and David Cameron – even argues that the the Tories face their biggest crisis in more than 100 years. The election is undoubtedly a serious setback for the party after a masterclass in poor election campaigning and complacency. The Conservatives are reeling from the profound shock of a campaign that began with an unprecedented 10% lead over Labour in Wales but ended with the loss of three Welsh seats as well as the party’s overall majority. Yet the Tories retain power in Westminster – unlike after the crisis elections of 1906, 1945, 1974 and 1997 – thanks to the unexpected revival of the Scottish Tories under Ruth Davidson and also improved their share of the vote to the highest level since 1983.

The initial autopsy on what went wrong has focused on a disastrous manifesto and the centrepiece social care proposals. Minor manifesto commitments on fox hunting and reversing the ivory ban caused disproportionate damage to the party’s image among younger, urban and more liberal voters who flocked to the party during the David Cameron years. This added to the disillusionment among more liberal Tory voters with the direction of the party since the Brexit vote, which triggered a sense that the liberal reforms of the Cameron years have been jettisoned. The party’s post-election alliance with the Democratic Unionist Party has added to these concerns. The viewpoint that the Tories have undergone an ideological lurch to the Right since Cameron’s resignation was covered in a high-profile post-election blog post by Emily Poole, a former special adviser to ex-Welsh Secretary Stephen Crabb explaining why she voted Labour in June. Poole has also blogged about the vitriolic abuse she received from Tories on social media in reaction to her original post.

There is also widespread anger in the party over Theresa May’s ill-fated presidential-style campaign. May’s antagonism towards the libertarian wing of the Tory party – dating from her days as Home Secretary and influenced by her controversial former adviser Nick Timothy – riled many of the party’s most experienced activists and influential pressure groups on the libertarian, free-market Right, such as Conservatives for Liberty. The unexpected timing of the election campaign also left the party reliant on recycling candidates from the 2015 election – many of whose views on Brexit now made them incompatible with constituencies and local party associations who voted a different way in the European referendum.

Drill deeper into the mechanics of the campaign and it’s now clear that the Tories were seriously disadvantaged in the ground war against Labour. Party strategists failed to realise the advantage that mobilisation of activists by Momentum would give Labour. Conservative Campaign Headquarters’ election planning does not seem to have accounted for the potential impact of the biggest non-party left-wing grassroots organisation in British politics since the heyday of CND. The successful Tory campaign formula of the 2015 general election revolved around the Road Trip initiative of busing young activists to key target seats to make up for the party’s growing deficit of local activists. The Tories had to campaign without Road Trip in 2017 because of the initiative’s role in the election expenses controversy and toxic association with the suicide of young Conservative activist Elliott Johnson. The party’s suspension of its Conservative Future youth wing in light of the Johnson tragedy meant it went into the election with no functioning youth wing. In an echo from Hillary Clinton’s failed presidential campaign, it also appears that the Tories were hindered by a defective campaign algorithm that diverted valuable resources in key battlegrounds such as London. There have been warnings about the weakness of the party machine since the 1990s when CCHQ culled many of its professional agents who were traditionally the backbone of the party’s campaign infrastructure. The need for radical reform is a constant topic on Conservative Home – the party’s equivalent of MumsNet or Pravda – with reformers like Kent agent Andrew Kennedy advocating for radical reform of local associations and campaigning.

Dolgellau, where Theresa May went for the fateful walk which inspired her to call a snap general election,

image by Shadow Shift, published in the public domain.

So with hindsight it’s not surprising that the Tories massively underperformed their expectations. Tory recovery depends on rebuilding an effective grassroots campaign organisation – although former minister Robert Halfon’s proposal for a Tory Momentum seems highly ambitious for a party hobbled by lack of activists. The party will also need to build on its improved standing among blue collar voters at the June 2017 general election to balance loss of support among liberal, urban voters disillusioned by Brexit and Theresa May and who might never return to the party without a ‘soft’ Brexit and a new, more liberal leader.

In Wales the Tories’ opportunity to recapture seats lies in successfully addressing Unionist concerns about devolved government under Labour and its Plaid Cymru and Liberal Democrat allies – notably Wales’s relative underperformance since devolution in health, education and social mobility – while appearing to move beyond its traditionally devo-sceptic rhetoric. It’s notable that one of the few Welsh Tory MPs to have a successful election in terms of an increased majority and percentage of the vote was Glyn Davies in Montgomeryshire. Davies – uniquely among Tories – favours both increased taxation powers for the Welsh Assembly Government and radically curtailing devolution of the Welsh NHS by linking Welsh health services with those in neighbouring England to improve patient outcomes.

The almost existential crisis in Tory circles should not lead observers to discount the party’s potential to adapt and recover. But recovery is not automatic. Theresa May is unlikely to fight another general election as party leader. CCHQ has – almost unnoticed – already overhauled its media operation and is undermining Jeremy Corbyn’s credibility on his tuition fees pledge with a slick social media attack ad campaign of the kind that was absent from the party’s general election arsenal. All, then, is still to play for.

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

Iain Lewis is originally from Ceredigion. He lives in south London and works in the media intelligence sector while maintaining a close interest in British political history.

If you liked this you may also like:

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…