Mike Parker challenges you not to be moved by the film Pride

18.09.14

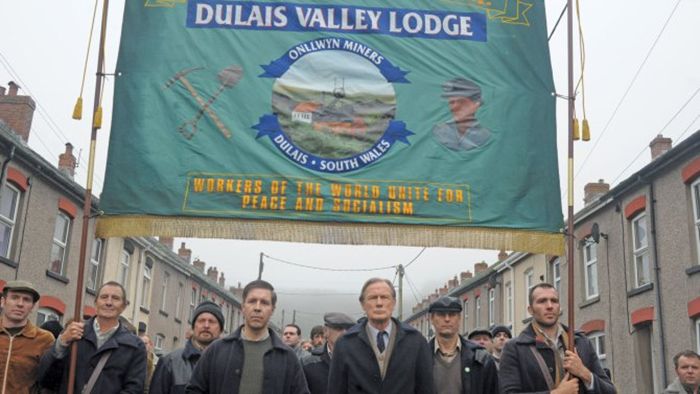

I was downright nervous about seeing Pride. The true tale of how a London Lesbians & Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) group twinned with the Dulais valley pit communities of south Wales in the 1984-5 Miners’ Strike, it could, I feared, leave me feeling doubly patronised. The worry wasn’t assuaged when I kept hearing it compared with 1997’s The Full Monty, a film that left me as cold as a January picket line.

Thankfully, all such fears were swiftly blown away. This is a film with a massive heart, an unashamed politics, a near-perfect cast and a thumping soundtrack that comes straight from my own pile of dusty vinyl. On the few occasions it threatened to tip into schmaltz, director Matthew Warchus swiftly tugged it – and us – back to the grey half-light of the mid 1980s, and captured its jagged polarity with unerring precision.

Like so many films before it, Pride is basically a set up of two wildly mismatched main characters, a will-they-won’t-they narrative dotted with small triumphs and knock-backs, before love conquers all in a thunderous finale. The difference here is that the two main characters are entire communities: the striking miners and their families in Onllwyn and Banwen, and the right-on young lesbians and gay men of London’s bedsit-land. Could two outliers of Margaret Thatcher’s “enemy within”, both struggling to find solidarity when it was in very short supply, come to realise that there was more uniting than dividing them?

Of course they could. The initial bridgehead was provided by ever level-headed miner Dai Donavan (Paddy Considine), who jumped straight in and accepted their offer of support without question. Almost too swiftly, it felt, but that is what apparently happened, and there were plenty of others who took a great deal more persuasion. One of the stand-out performances of the film was Lisa Palfrey as widow Maureen, who, with her two gruff adult sons, refuses to accept the LGSM contingent, and pursues her own thin-lipped vendetta to spoil the party.

She is in the minority too as one of the few Welsh actors playing any of the major Welsh characters. This was another factor contributing to my pre-screening nerves, but save for the odd dropped dipthong, non-Welsh members of the cast cope admirably. Imelda Staunton gives her feisty damnedest as Hefina, while Bill Nighy is mesmerising in his understatement as bookish Cliff. Between them, they conjure one of the most quietly affecting scenes in the entire film, when truths are mined from the deepest seam as they spread and cut a mountain of margarine sandwiches.

Top marks too in the Welsh impression stakes to Irish actor Andrew Scott. His character, Gay’s The Word bookshop manager Gethin, had fled Rhyl sixteen years earlier and never been back. Gethin is the sole wholly fictional figure in the story, pivotal as the only character with one foot in Wales, the other in gay London. Scott’s gossamer intensity elevates Gethin to far more than a mere plot device however; when he can finally bubble with joy at reconciling his sexuality and his nationality, it is a glorious moment. His pilgrimage home to Rhyl and his unforgiving mother is less successful, for there are just too many other issues bursting for our attention.

The film’s central character, young Ulster firebrand Mark Ashton, is played beautifully by New Yorker Ben Schnetzer. Ashton, who died aged 26 only a couple of years after the strike, was a gorgeous dervish of leftie queer agitprop. Everyone fell in love with Mark, and while it was supremely easy to see why, the film gives us scant idea as to how. Pride is unflinching in its politics, but gets distinctly bashful when it comes to sex. A modesty curtain hangs throughout over the enmeshed love lives of the main protagonists, as if a gang of young gay men newly out in London can find nothing they’d rather do than endlessly rattle buckets for miners; pur-leese!, as someone would have said. To offset any accusations of prudishness, a few dildoes and fetish bars are thrown in, but only as comedy foils for raucous, wide-eyed Welsh wives. Ritual desexualisation is a regular trope of queer films that aspire to a mainstream audience, but this is so much better than most; the comparative coyness seems out of synch with its mood and ambition.

The first time I heard this remarkable story was at an NUS lesbian and gay conference in some sticky-floored Nelson Mandela Building in the late 80s. A smoky roomful of us, all hair gel and hormones, was shown a video made by LGSM in 1986, called Dancing in Dulais (it’s on YouTube). Watching it again, decades later, it’s striking how closely the film sticks to the script, and how accurate are the portrayals of the main players, but there are subtle differences.

Pride succeeds terrifically in evoking the politics of the age – and not just of the gays and miners, but also in knowing asides into feminism and separatism, the freezing shadow of AIDS and the hiraeth/heartache of a Wales with the shit kicked out of it. The 1986 video puts it all in far grainier context; the splinter-group sectarianism of the left, the dead-weight earnestness, the interminable bloody meetings.

But oh my goodness, the fun and comradeship too. (Almost) nothing gets the blood pumping more urgently than being united on the right side against powerful, brutal opposition; Pride luxuriates in that joy. It conjures a happy – and mostly true – ending out of the misery of the miners’ defeat, and sends those of us of a certain age and a certain background out of the cinema with our danders up in a way that we’d long thought impossible. It made me laugh until I cried, and cry until I sobbed. Some of the laughs and most of the tears were undoubtedly for my own lost youth and cast-iron certainties, but I defy anyone – boo hiss flint-hearted Tories excepted, of course – to resist.We feature further reviews and analysis in the magazine. See our contents pages in the archives section and you can buy issues here.